Space & Astronomy

13 min read

Massive Iron Bar Found in Ring Nebula: Clue to a Destroyed Planet?

Interesting Engineering

January 18, 2026•4 days ago

AI-Generated SummaryAuto-generated

Astronomers discovered a massive, bar-shaped cloud of iron atoms within the Ring Nebula, previously undetected. This structure, potentially as massive as Mars, challenges current understanding of stellar death and nebula formation. One hypothesis suggests it may be the remnants of a destroyed planet that ventured too close to the dying star.

Have you ever seen a cloud made of iron? You may not believe it, but deep inside a nebula that astronomers have studied for centuries, researchers have uncovered a massive bar-shaped cloud made almost entirely of iron atoms.

This glowing shell of gas left behind by a dying star had gone unnoticed despite hundreds of years of observation. Stretching across a distance roughly 500 times the size of Pluto’s orbit and containing as much iron as the planet Mars, the newly found “iron bar” raises deep questions about how stars die, how nebulae form, and what happens to planets caught in the chaos.

Interestingly, even scientists have no clue how this iron bar came into existence. “At present, there seem to be no obvious explanations that can account for the presence of the narrow bar,” the researchers note.

This discovery shows that even well-known cosmic objects can still surprise us.

The iron bar is a cosmic wonder

The Ring Nebula has been studied since 1779, using many of the world’s most powerful instruments, including the James Webb Space Telescope. Yet astronomers had never seen this iron structure before. The reason is that most earlier observations looked at the nebula in limited wavelengths or focused only on certain regions.

What changed this time was a new instrument called WEAVE, installed on the 4.2-metre William Herschel Telescope in Spain. WEAVE includes a special mode called the Large Integral Field Unit, or LIFU. Instead of taking light from just one point, LIFU uses hundreds of optical fibers to collect light from every part of the nebula at once.

This allowed the researchers to split the nebula’s light into its component colors—known as spectra—across the entire object and across all optical wavelengths. “By obtaining a spectrum continuously across the whole nebula, we can create images of the nebula at any wavelength and determine its chemical composition at any position,” Roger Wesson, lead researcher and an astronomer at Cardiff University, said.

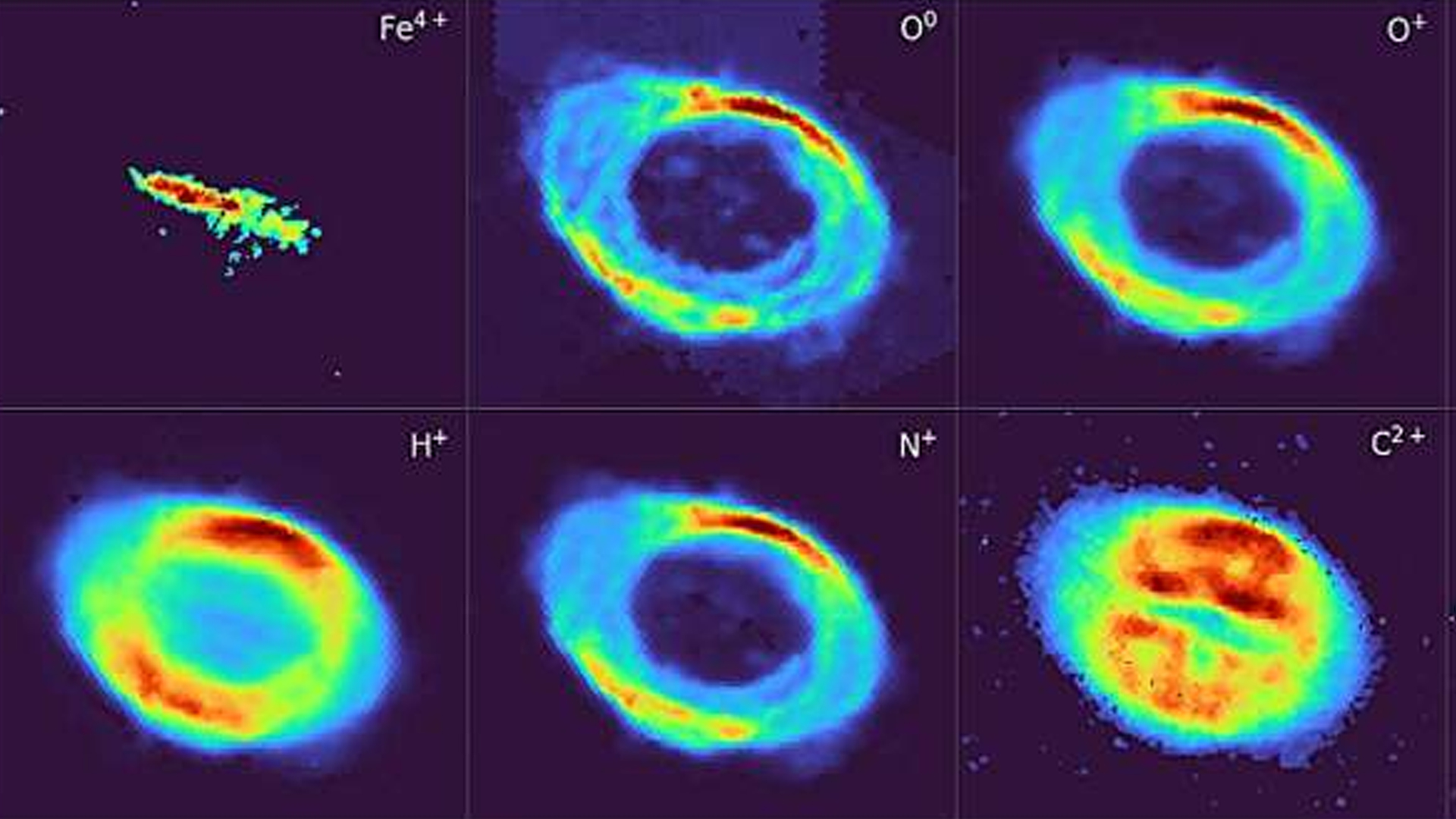

When the researchers processed the data and scanned through images corresponding to different elements, something immediately stood out. Right in the middle of the nebula was a clear, narrow strip glowing strongly in the light emitted by ionized iron atoms.

This “bar” fits neatly inside the nebula’s inner elliptical ring and has no obvious counterpart in images taken at other wavelengths. Plus, the amount of iron was also startling. Based on the brightness of the iron emission, the team estimated that the mass of iron in the bar is comparable to that of Mars.

Finding such a large concentration of iron in this precise shape is difficult to explain using existing models of how planetary nebulae form. Adding to the mystery, the study authors note, “the extent to which iron in this bar is depleted is presently unclear.” This makes the iron bar discovery even more intriguing.

One discovery, many possibilities

At the moment, scientists do not know how the iron bar formed. One possibility is that it records a previously unknown stage in how the dying star expelled its outer layers, revealing new details about the physics of stellar mass loss.

A more dramatic idea is that the iron could be the remains of a rocky planet that wandered too close to the star during its expansion and was vaporized into a curved arc of hot plasma.

However, the researchers still do not know whether other elements are mixed in with the iron. This missing information makes it hard to choose between different explanations. To solve this, the researchers plan to observe the Ring Nebula again using WEAVE at higher spectral resolution, which will allow them to separate subtle signals from different atoms more clearly.

Moreover, WEAVE will observe many more ionized nebulae across the Milky Way over the next five years, and astronomers suspect the Ring Nebula may not be unique.

“The discovery of this fascinating, previously unknown structure in a night-sky jewel, beloved by sky watchers across the Northern Hemisphere, demonstrates the amazing capabilities of WEAVE. We look forward to many more discoveries from this new instrument,” Scott Trager, one of the study authors and a scientist at the University of Groningen, said.

The study is published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Rate this article

Login to rate this article

Comments

Please login to comment

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!