Health & Fitness

17 min read

Maya's Ancient Eclipse Predictions: Unlocking the Dresden Codex

Earth.com

January 20, 2026•2 days ago

AI-Generated SummaryAuto-generated

New analysis of the Dresden Codex, an ancient Mayan manuscript, reveals its eclipse tables offered centuries of accurate warnings. Researchers discovered a sophisticated system of overlapping calculations and resets, maintaining precision for long-term astronomical predictions. This finding reshapes understanding of Mayan scientific capabilities, demonstrating a practical blend of observation, arithmetic, and meticulous copying.

An ancient Mayan manuscript that includes a set of handwritten numbers, known as the Dresden Codex, turns out to have been far more than symbolic record keeping.

New analysis shows the Dresden Codex figures could keep eclipse warnings usable for centuries, pointing to a level of long-term precision that reshapes how Maya science is understood.

It contains a carefully organized sequence of lunar and eclipse calculations that appears to have been maintained and adjusted over many generations.

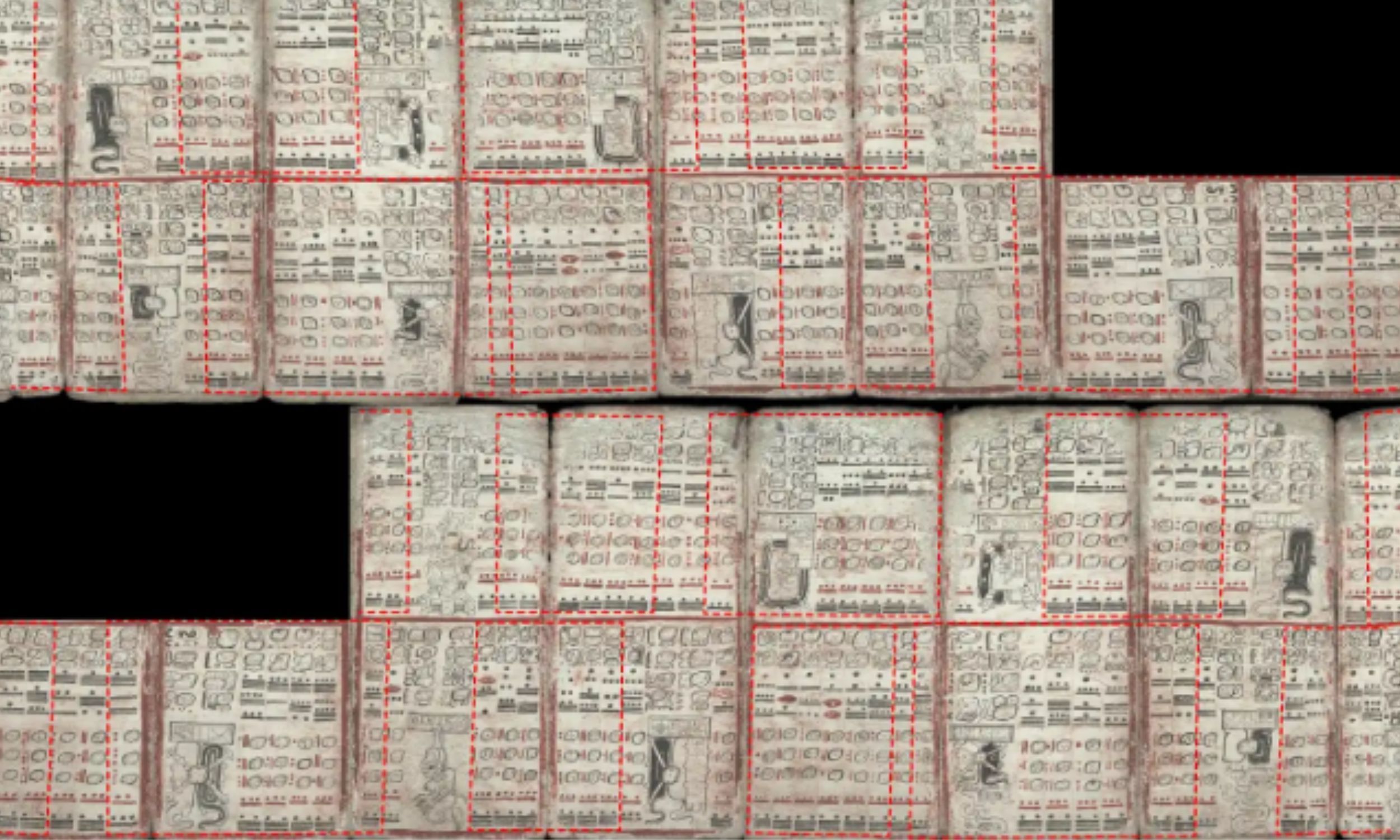

Folded pages of the Dresden Codex preserve eclipse and Venus calculations in one of only four surviving Maya manuscripts.

Careful reanalysis at the University at Albany in the State University of New York (SUNY) mapped the table as a working tool.

John Justeson, a SUNY emeritus professor, led the work, and his research centers on Maya writing systems.

That focus helps explain how a small set of numbers could stay useful across many generations of observers.

Dresden Codex and lunar months

Across 405 lunar months, the eclipse table marks 69 lunations, one new-moon cycle to the next, as key checkpoints.

Solar eclipses only happen at new moon, and they cluster near lunar nodes, where the Moon crosses Earth’s orbital plane.

Some marked dates would have produced no local darkness, because the alignment can miss a region by hundreds of miles.

Even so, the system gave daykeepers – calendar specialists who maintained sacred day counts – a warning window rather than a map of shadow paths.

Resetting the table at its end sounds neat, but small timing mismatches would stack up over decades.

Each lunar month lasts about 29.5 days, so a count built from whole days slowly slides off the sky.

Over many cycles, a predicted eclipse season could arrive a day early or late, and observers would notice.

That drift makes a single unbroken table risky, especially when people depend on it for ceremony planning.

Overlapping tables, fewer errors

Instead of starting fresh at the last line, daykeepers could begin the next copy before the old one finished.

The new paper from SUNY points to two reset points – at 358 and 223 months – that pull dates back on track.

One option corrects small errors often, while the other makes a larger adjustment after many repeats of the same span.

Modeling suggests the combined method could hold the calendar within 51 minutes over 134 years, which sets a clear limit.

Two calendars, one anchor

Maya astronomy sat inside everyday record keeping, because priests tracked both farming seasons and sacred day names.

The divinatory calendar, a 260-day sacred count for naming days, ran beside a 365-day civil year.

“This suggests that the 405-month eclipse table had emerged from a lunar calendar in which the 260-day divinatory calendar commensurated the lunar cycle,” wrote Justeson.

Tying sky events to named days meant an eclipse warning was not just science, but also social timing.

From lunar notes to eclipses

Monthly moon watching likely came first, because eclipse signs only make sense when people already track new moons carefully.

Justeson and Lowry argue the table began as a running lunar count, with each month assigned 29 or 30 days.

“The eclipse table seems to have been a repurposed revision of a less complex table, which listed 405 successive lunar months,” wrote Justeson.

If the table started as bookkeeping, later editors could add eclipse markers without rewriting the whole calendar from scratch.

A historical reference point

A likely starting point for the surviving table sits around 1083 or 1116 CE, matching eclipse seasons in northern Yucatan.

On July 11, 1991, a total solar eclipse crossed Mexico and Central America in mid-afternoon.

Later retellings sometimes place that blackout in 1999, but the documented path belongs to the 1991 event.

Using overlapping resets, a calendar specialist could keep the ancient table aligned well enough to flag such eclipse seasons centuries later.

Earlier calendar evidence

Painted fragments at San Bartolo show Maya scribes writing a day name between 300 and 200 BCE.

The authors report a record called 7 Deer, which fits the 260-day count that later appears in the codices.

Dating came from sealed construction layers in the Las Pinturas pyramid, so the calendar mark sits in firm context.

That early evidence makes it easier to see how eclipse prediction grew from long practice rather than sudden inspiration.

Lessons from the Dresden Codex

Scholars have studied the Dresden numbers for more than a century, yet the table’s reset logic stayed unclear.

The new reading treats scribal copying as part of the design, because overlap turns each new table into an update.

Copying errors still matter, and the researchers note places where a dot or bar mistake can move totals by days.

Because so few Maya books survived colonial burnings, the method will stay hard to test beyond this one manuscript.

Taken together, the evidence shows Maya specialists built a practical eclipse warning system by blending observation, arithmetic, and careful copying.

Modern readers gain a clearer view of Indigenous science, while the missing codices remind us how much context is gone.

The study is published in Science Advances.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–

Rate this article

Login to rate this article

Comments

Please login to comment

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!