Economy & Markets

172 min read

Lung Organoids: Precision CAR T Cell Therapy Testing Ground

Nature

January 21, 2026•1 day ago

AI-Generated SummaryAuto-generated

Researchers developed lung tumor organoids (TOs) that replicate patient tumors' genomic and proteomic profiles. These TOs successfully modeled patient responses to chemotherapy and CAR T cell therapy. The platform allows for personalized testing of CAR T cells, assessing efficacy and potential off-target toxicities. This approach offers a promising tool for precision medicine in lung cancer treatment development.

Establishment and culture of lung TOs and matched healthy lung organoids

We initiated TO and healthy lung organoid (HO) cultures from 12 patients undergoing surgical resection of lung tumours (Fig. 1a, Extended Data Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 1). To improve TO culture, we applied mechanical dissociation to preserve cell–cell contacts essential for TO formation19,20 (Methods). Cultures were initiated either immediately or following tissue freezing (<6 months) (Supplementary Table 1). The basal culture medium contained B27, nicotinamide, N-acetyl L-cysteine, A83-01, L-glutamine, SB202190, Noggin, EGF and R-Spondin. To enhance efficiency, we tested combinations of FGF2, FGF7, FGF10, Wnt and CHIR, addressing tumour-specific requirements for Wnt activation and fibroblast support14,21 (Extended Data Fig. 1b). TOs were considered successful if they were propagated ≥6 months, achieved in six patients. Long-term cultures from four patients showed overgrowth of healthy cells (Extended Data Fig. 1c). Primary tumour cells from two patients expanded for 2 months but declined, yielding a 50% success rate (Extended Data Fig. 1c). No TOs were established from eight samples frozen >6 months, underscoring the importance of timely processing (Extended Data Fig. 1c). By contrast, HO generation achieved a 100% success rate regardless of freezing duration (Extended Data Fig. 1c). The histological and clinical profiles of patients reflected the full spectrum of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) heterogeneity, with a slight enrichment of higher tumour stages (Union for International Cancer Control, UICC) in the short-term frozen sample group (Extended Data Fig. 1d and Supplementary Table 1). Freezing duration, rather than tumour content or UICC stage, was the main determinant of TO success (Extended Data Fig. 1e,f). The success rate of TO cultures from immediately processed samples was 60%, consistent with a retrospective prediction (Extended Data Fig. 1g).

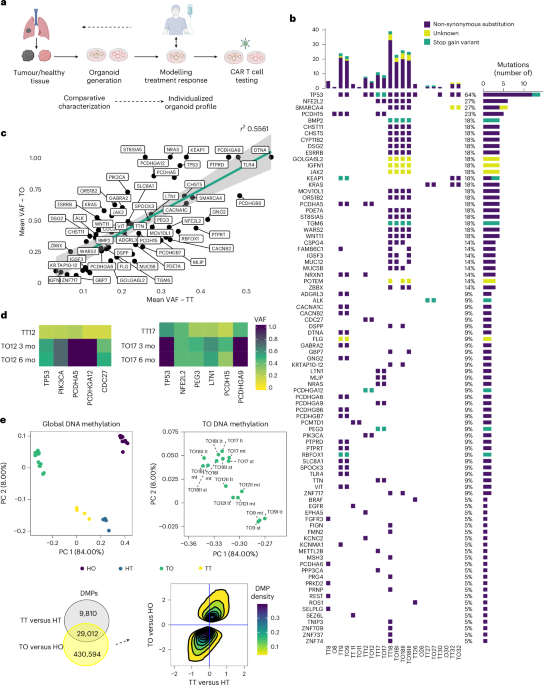

Genomic and epigenomic landscape of tumours is preserved in TOs

To ensure that TOs retained the genomic and epigenomic characteristics of their parental tumours (tumour tissue, TT), we performed comparative DNA sequencing and methylation analyses. We used a concise sequencing panel (National Network Genomic Medicine Lung Cancer) panel for key lung cancer-associated genes and a targeted sequencing (TDS, see Methods and Supplementary Table 2a) panel spanning >1,000 mutation-rich regions. Panel deep sequencing and whole-exome sequencing (WES) provided comprehensive molecular profiling (Fig. 1b–d, Extended Data Fig. 1h and Supplementary Table 2). Eight TO lines from six patients exhibited a mutational landscape consistent with their parental tumours, including common NSCLC mutations such as TP53, KEAP1, PIK3CA, SMARCA4 and EGFR (Fig. 1b). Organoids from patients 8, 11, 26 and 30 (O8, O11, O26 and O30) lost primary tumour mutations, reflecting healthy cell overgrowth (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 1h). HOs were negative for cancer-associated mutations (Extended Data Fig. 1h). Variant allele frequency (VAF) varied between TTs and TOs, indicating preserved heterogeneity and subclonality (Fig. 1c). In TO culture, non-epithelial cells are typically outgrown by epithelial cells under epithelial-favouring conditions22. Consequently, TOs showed an enrichment of most mutations, as seen by the slope of the linear regression when comparing the mean VAF of all TO mutations with that of all TTs (Fig. 1c). This analysis suggested a VAF enrichment effect (enrichment of tumour epithelial cells), with mutations such as TP53, NRAS and KEAP1 becoming more dominant in TOs over time, reflecting clonal enrichment (Fig. 1c,d). Conversely, mutations with lower VAFs than predicted by the linear regression probably indicated mutation loss and outgrowth of subclones under selective pressure (Fig. 1c).

Epigenomic profiling based on DNA methylation distinctly separated TTs from healthy lung tissue (HT) along the first principal component (PC1), which accounted for 84% of total variance (Fig. 1e, top left). The differences were even more pronounced between TOs and HOs. Epigenetic changes induced by TO culture were smaller and mapped to PC2, explaining 8% of variance (Fig. 1e, top left). Notably, 75% of differentially methylated positions (DMPs) between TTs and HTs remained differential between TO and HO, highlighting preservation of the epigenetic profile from TTs in the corresponding TO (Fig. 1e, bottom left). While a large number of DMPs (430,594) were unique to the TO versus HO comparison, these DMPs followed the same hypo- or hypermethylation trend as detected ex vivo (Fig. 1e, bottom right). TOs from the same patient clustered together despite different additives, indicating growth-factor-independent epigenomic profiles (Extended Data Fig. 1i). Longitudinal TDS and methylation analyses demonstrated that genomic and epigenomic profiles of TOs captured the mutation landscape and methylome of primary tumours, maintaining identity over time (Fig. 1d,e top right).

Lung TOs maintain histological, proteomic and phenotypic signatures of parental tumours

To confirm the tumour identity of TOs, we performed immunohistochemistry (IHC) on NSCLC markers: thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF1), cytokeratin 5/6 (CK5/6), cytokeratin 7 (CK7), tumour protein 40 (p40) and tumour protein 63 (p63). TOs with preserved mutations maintained the expression of key histological markers largely mirroring parental tumours (Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 2a), as shown by histoscores (H-scores) (Fig. 2b). Squamous cell carcinomas (TT12, TT17 and TT18) were negative for TTF1, variable for CK7 and positive for CK5/6, p40 and p63, patterns preserved in TO12, TO17 and TO18 (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 2a). Lung adenocarcinomas (ACs) (TT9, TT11 and TT24) showed consistent CK7 expression, variable TTF1 and absence of CK5/6, p40 and p63, reproduced in TO9 (Fig. 2a,b). TOs overgrown by healthy cells or short-term cultures showed mixed patterns (Extended Data Fig. 3). Healthy tissues consisted of TTF1+ alveolar type II (ATII) cells and club cells, CK5/6+, p40+, p63+ basal layers of bronchioles and CK7+ upper layers of bronchioles (Extended Data Fig. 3).

To assess cellular composition of our organoid system, we performed flow cytometry. Unlike parental tissues, which contained multiple cell types, both TOs and HOs consisted exclusively of EPCAM⁺ epithelial cells (Extended Data Fig. 2b,c). We performed liquid chromatography-based mass spectrometry (LC–MS) on matched TT, TO, HT and HO samples. A total of 9,945 proteins were detected (Fig. 2c, Extended Data Fig. 2d, Supplementary Table 3). Functional analysis revealed that TO-unique proteins were primarily involved in cell cycle processes, while HO-unique proteins were substantially enriched in polarization and respiratory cilium organization23 (Extended Data Fig. 2e). To account for the epithelial-only nature of our organoid system, we excluded non-epithelial proteins from comparative proteomic analyses (Extended Data Fig. 2f and Supplementary Table 4). Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) visualization revealed separation among sample groups, with TTs, HTs, TOs and HOs forming distinct clusters (Fig. 2d). HT and HO samples formed more compact clusters, while TT and TO samples displayed greater heterogeneity, consistent with their tumoural origin (Fig. 2d). HTs and HOs showed comparable pathway enrichment profiles, supporting the suitability of HOs as healthy controls (Fig. 2e and Extended Data Fig. 2g). Comparative analysis identified multiple lung cancer-related proteins that were differentially expressed between TTs and HTs, as well as between TOs and HOs (Fig. 2f and Extended Data Fig. 2h). Hierarchical clustering demonstrated proteomic similarity within tumour- and healthy-derived sample pairs (Fig. 2g and Extended Data Fig. 2i). Proteogenomic correlation analysis showed that pathway enrichment for TTs versus HTs and TOs versus HOs focused on pathways associated with the most prevalent mutations (Supplementary Table 4). Mutations detected by WES were preserved in TOs, with VAF enrichment comparable to that observed in TDS (Fig. 2h; for TDS results, see Fig. 1b–d). Mucin gene mutations, abundant in both TTs and TOs, were associated with enrichment of pathways related to ECM proteoglycans, O-linked glycosylation and amyloid fibre formation (Fig. 2h). Pathway enrichment linked to lung cancer-specific mutations was similarly preserved in TOs (Extended Data Fig. 2j). In conclusion, TOs and HOs are distinct (Extended Data Fig. 2k) and TOs largely preserve the proteomic landscape of their parental tumour tissues, while HOs retain the proteomic signatures of their corresponding healthy tissues. Moreover, our data demonstrate that genomic alterations are effectively reflected in corresponding proteomic signatures, underscoring the biological relevance of our organoid system.

Patients’ treatment response can be modelled with lung TOs and correlates with proteome profiles

Patients selected for this study exhibited lung tumour recurrence and failure of multiple treatment lines (Extended Data Fig. 4a). To assess whether TOs can reflect treatment resistance observed in the original tumours, we applied the same therapies patients had received to the corresponding TOs. Responses were monitored over time using live-cell imaging (Fig. 3a). At the experimental endpoint, cell viability was quantified using an ATP-based luminescent assay. Dose–response experiments were conducted to determine IC50 values (the drug concentration that reduces cell viability by 50%) as a measure of treatment response (Fig. 3b and Extended Data Fig. 4b). A549 (AC) and NCI-H292 (mucoepidermoid) cell lines served as references to relate TO responses to clinical outcomes. HOs exhibited predominantly intermediate or resistant responses, limiting their utility as non-tumour controls (Extended Data Fig. 5). Patient 9 and patient 18 were resistant to carboplatin, either as first-line treatment (patient 9) or as neoadjuvant chemotherapy (patient 18). This resistance was reflected by IC50 values in the corresponding TOs, which approximated those of carboplatin-resistant A549 and carboplatin-intermediate NCI-H292 controls (Fig. 3b,c). Conversely, patient 17 showed a partial response to the carboplatin combination regimen before surgery, and TO17 exhibited the lowest carboplatin IC50 (Fig. 3b). Drug activity Z scores, aligned to the CellMiner database, further validated these findings, showing that TO9, TO17 and TO18 accurately modelled clinical responses to carboplatin in vitro (Fig. 3c, left). Patient 9 partially responded to docetaxel as a second-line treatment, and this response was mirrored by TO9, which exhibited the highest drug activity Z score compared with experimental controls and database cell lines (Fig. 3c, middle). TO9 showed an intermediate response to pemetrexed, matching the clinical outcome (Fig. 3c, right). Similarly, the partial response of patient 17 to nab-paclitaxel was reflected by TO17, which was sensitive in vitro (Fig. 3d, left). We tested cisplatin on TO12 and observed a high in vitro drug activity Z score, comparable to sensitive cell lines (Extended Data Fig. 5). In addition, TO18 harboured a SMARCA4 mutation, associated with resistance to chemotherapy24. Testing nab-paclitaxel and palbociclib, a CDK4/6 inhibitor, on TO18 yielded drug activity values similar to resistant lines, suggesting limited efficacy (Fig. 3d, left, and Extended Data Fig. 5). Furthermore, TO9 was resistant to erdafitinib, an FGFR inhibitor, probably due to a KEAP1 mutation in TT9 and TO9, previously associated with acquired resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors in lung cancer25 (Fig. 3d, right). To explore therapy personalization with TOs, we screened the proteomics dataset for proteins associated with resistance to platinum-based chemotherapies (Extended Data Fig. 4c). Platinum-resistant TOs (TO9 and TO18) clustered together, whereas sensitive TOs (TO12 and TO17) confirmed proteomic profiles consistent with therapy response (Extended Data Fig. 4c). We also identified resistance-associated proteins NRAS, PROM1, HDAC3 and EIF2AK3, overexpressed in resistant TOs26,27,28 (Fig. 3e). HMGB1, a driver of chemoresistance29,30, was highly expressed in TO9, suggesting it as a potential target for inhibitory therapies to enhance carboplatin response (Fig. 3e). These results underscore the potential of lung TOs to model patients’ treatment responses and to guide decisions on advanced therapies.

Lung TOs as a platform for testing CAR T cell therapy

We developed a pipeline to screen TTs, HTs and matched organoids (TO/HO) for TAAs evaluated in lung cancer CAR T cell trials (Supplementary Table 7). Identified TAAs were targeted with CAR T cells, engineered by exchanging the single-chain variable fragment (scFv) from a curated library. The efficacy of CAR T cells was assessed using TOs, while HOs served for potential on-target, off-tumour toxicities (Fig. 4a). In most cases, TAA expression in HOs and TOs resembled their parental tissues (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 1a). TAA expression was specifically semi-quantified in tumour cells from TTs, respiratory epithelium from HTs and organoid cells from TO/HO, yielding comparable H-scores (Fig. 4c, Extended Data Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 1b). A notable exception was the hepatocyte growth factor receptor (cMET), overexpressed in organoids and not matching the corresponding primary tissues (Extended Data Fig. 6a). TAAs overexpressed in TOs versus HOs were selected as targets for CAR T cell therapy. Among TAAs evaluated, mesothelin (MSLN) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) were excluded for low/non-differential expression. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) was a candidate in patient 9 but was not tested owing to unavailable CAR constructs. Mucin-1 (MUC1) was highly expressed in both TO9 and HO9, and across other HOs, disqualifying it as a tumour-specific target. Conversely, HER2 showed differential expression in TT9, TT17 and TT18 versus matched HTs, emerging as a promising target (Fig. 4c). Matching TOs and HOs generally showed corresponding HER2 H-scores, except for TO18, which was heterogeneous, with HER2-high and HER2-negative organoids (Extended Data Fig. 6b). PDL1 was a candidate in patient 12, with higher H-scores in TTs and TOs than in healthy counterparts. CAR T cells targeting these TAAs were generated using a virus-free CRISPR-engineering approach31, which disrupted the T cell receptor alpha constant chain (TRAC) locus. This modification eliminated endogenous T cell receptor (TCR)/CD3 expression while enabling stable CAR expression. CAR expression on the T cell surface was detected via a c-Myc tag fused N-terminally to the scFv. Second-generation CD28-CD3ζ CARs (CD28z) targeted HER2 and PDL1. Non-targeting control CARs against CD19 and EGFRvIII were also generated (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 8).

CAR T cells demonstrated specific activation upon target recognition, indicated by upregulation of the activation markers CD137 and CD154, observed only after coculture with TOs or HOs (Extended Data Fig. 7a). Despite varying HER2 levels in TO9, TO12, TO17 and TO18, all TO samples comparably activated HER2-28z CAR T cells, unlike non-targeting CD19-28z controls (Fig. 4e). Activation was consistent in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Activation yielded production of IFNγ, TNF and IL-2 (Supplementary Fig. 2b), with comparable cytokine levels from CD4+ HER2-28z CAR T cells across TO samples (Fig. 4f, top). By contrast, CD8⁺ CAR T cells showed significantly elevated cytokine production in response to TO12 compared with other TOs (Fig. 4f, bottom). Similarly, HOs expressed sufficient HER2 to trigger activation and cytokine production comparable to TOs (Extended Data Fig. 7a,b). PDL1-28z CARs were activated by all TO and HO samples, except for TO9, which had the lowest PDL1 H-score (Extended Data Fig. 7a,b). For PDL1-28z CARs, cytokine production was lower than with HER2-28z CARs (Extended Data Fig. 7b). The differential cytokine production observed here may involve various mechanisms, including but not limited to potential interactions between PDL1-targeting CAR activity and PDL1-mediated signalling pathways.

To determine whether CAR T cell activation resulted in effective organoid killing, we used bulk or purified CAR T cells in killing assays (Fig. 5a and Extended Data Fig. 8a,b). TOs/HOs were cocultured with prestained CAR T cells at three effector-to-target (E:T) ratios: high, medium and low (Methods). Cell death was tracked using NucRed Live/Dead staining for real-time TO viability (Fig. 5b). Specific killing was quantified as a reduction in organoid surface. Advanced image analysis (Supplementary Table 9) quantified intact, living organoid area (Extended Data Fig. 8c–e). We evaluated HER2-28z CAR T cell cytotoxicity in all TO and HO samples.

At high E:T ratios, substantial specific killing was observed in TOs and HOs (Fig. 5c and Extended Data Fig. 9a-b). Comparable killing in TOs and HOs from patients 17 and 18 excluded them as candidates for HER2-targeted therapy using this CAR. By contrast, TO9 and TO12 exhibited dose-dependent HER2-CAR T cell killing, with clear differential effects relative to their matched HOs. Notably, TO9 showed particularly robust responses, with 53% of specific killing at medium E:T ratios and 14.6% at low E:T (Fig. 5d).

To further characterize individual killing responses, we analysed cytokine profiles from killing assay supernatants. Consistent with prior flow cytometry data, HER2-28z CAR T cells produced activation-associated cytokines (IFNγ and TNF), even when killing was minimal at 30 h (Fig. 5e and Extended Data Fig. 9d). These findings indicate that similar activation and cytokine levels across TOs and HOs do not necessarily translate into effective ex vivo killing, suggesting that cytotoxicity is influenced by patient-specific resistance mechanisms captured by this model. TO9 triggered CAR T cell activation levels comparable to other TO samples but showed superior susceptibility to killing. Its high HER2 H-score (254.9) suggests that TAA density may be a critical determinant of effective killing. In addition, basal IL-8 levels, previously implicated in immune evasion by cancer cells32, were detected in TO and HO supernatants in the absence of CAR T cells, with TO9 exhibiting the lowest IL-8 levels among all samples (Fig. 5e). TO12, by contrast, showed unexpectedly high killing despite a low HER2 H-score (32.8), accompanied by elevated HER2-28z cytokine production (Fig. 4f). Notably, TO12 was the only organoid that secreted pro-inflammatory IL-6 even in absence of CAR-T cells (‘No CAR’, Fig. 5e), recapitulating IL-6 secretion observed in the corresponding tumour tissue (Extended Data Fig. 9e). To identify additional factors influencing CAR T cell efficacy, we analysed the proteome across TOs. TO9, which showed the most efficient killing, exhibited the lowest expression of autophagy-related proteins (Supplementary Fig. 3a), a pathway previously associated with resistance to T-cell-mediated killing33. It also had the lowest immune evasion-associated proteins (Supplementary Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 5). We next assessed the surface expression of immune checkpoint inhibitor PDL1 by flow cytometry. Baseline PDL1 levels were comparable across all TO and HO samples. However, upon IFNγ stimulation, mimicking inflammatory, killing-like conditions, TO9 showed minimal PDL1 upregulation, whereas TO12, TO17 and TO18 exhibited strong induction (Fig. 5f). HO samples showed the highest PDL1 induction overall (Fig. 5g). We tested whether PDL1-targeting CARs could serve as an alternative. PDL1-28z CARs induced target cell killing at high E:T ratios in all samples (Fig. 5h). However, only TO12 showed dose-dependent differential killing compared with its matched HO. Notably, TO12 also exhibited the highest basal PDL1 H-score (Fig. 5i). To confirm killing specificity, we included EGFRvIII-28z CAR T cells as a control. No off-target killing was observed (Supplementary Fig. 3c). To demonstrate the platform’s scalability and feasibility within a clinically relevant timeframe, we established HOs and TOs from patients 27 and 32 within 3 months of surgery. Targeted sequencing confirmed that TOs retained tumour-specific mutations (Extended Data Fig. 1h). When treated with HER2-28z and PDL1-28z CARs, patient 27 showed differential killing of TOs versus HOs with both constructs (Extended Data Fig. 10a,b), suggesting potential responsiveness. By contrast, patient 32 did not exhibit substantial killing.

To assess the relationship between CAR T cell cytotoxicity and target density, we examined the correlation between HER2 expression and maximum killing across TOs. Correlation analysis suggested a positive trend (Spearman ρ = 0.771, P = 0.103; Extended Data Fig. 10c). Linear regression showed that the HER2 H-score accounted for 62% of the variance in maximum CAR T cell killing (R² = 0.62; Extended Data Fig. 10c), consistent with a strong but non-exclusive role of target density. Importantly, several TO lines deviated from predicted killing based on the HER2 H-score, underscoring that HER2 expression correlates with CAR T cell cytotoxicity but alone does not predict efficacy (Extended Data Fig. 10d). Similar trends were observed for PDL1 CAR T cell killing (Extended Data Fig. 10e,f). These patient-specific deviations further highlight roles for the cytokine milieu and broader tumour-intrinsic programs in determining therapeutic outcomes.

Our platform captures patient-specific CAR T cell responses shaped by factors beyond target antigen density. It identifies strong CAR T cell responders even without clear activation differences, reinforcing that activation is necessary but not sufficient for efficacy. By providing individualized insights into determinants of CAR T cell performance, the platform supports the optimization of CAR T cell therapies in lung cancer.

We developed a patient-specific preclinical platform for testing standard-of-care treatment and CAR T cells using lung TOs derived directly from primary tumour material. The robust viability and reproducibility of our lung TO cultures support longitudinal studies of CAR T cell kinetics, resistance mechanisms and dynamic alterations in tumour-intrinsic immune escape pathways, including immune checkpoint and cytokine signalling. Key features of tumour epithelial cells relevant for microenvironmental interaction, such as ECM pathways and cytokine production, are preserved. This set-up enables iterative optimization of CAR constructs within a stable patient-specific context. To demonstrate clinical feasibility, we show that TO establishment, molecular characterization and CAR T cell testing can be completed within 3 months of surgical resection, an actionable timeline for personalized therapy evaluation. Compared with existing preclinical models (Supplementary Table 6), our approach offers: a robust protocol applicable across diverse lung cancer subtypes; matched HO controls for specificity assessments; scalable TAA screening without prior antigen selection; and functional correlation of CAR T cell responses with patient-specific molecular profiles. Future iterations will incorporate stromal components and microfluidic systems to model CAR T cell trafficking. Lung TOs preserved key mutations, histological features and molecular signatures of their parental tumours and mirrored patient responses to chemotherapy, underscoring their potential for predicting therapeutic outcomes. Crucially, our data show that CAR T cell cytotoxicity is not solely dictated by antigen expression or T cell activation, but reflects a multifactorial interplay involving antigen density, cytokine milieu and additional immunoregulatory signals. These insights reinforce the value of integrating TO-based functional assays into CAR T cell testing workflows for precision immunotherapy development. Our protocol achieved a 50% success rate for lung TO establishment, exceeding prior reports12,13,14,15. This improved efficiency may reflect optimized tissue dissociation and the inclusion of Wnt, CHIR and FGF2, which support alveolar type II cell growth, an epithelial lineage implicated in subsets of NSCLC34. We also found that freezing primary tumour tissue before culture negatively impacted establishment rates, supporting the use of fresh material followed by cryopreservation of successfully established TOs.

Our immunohistochemical analyses confirmed that lung TOs preserve hallmark NSCLC features. Epigenomic features were largely preserved as well. In addition, we provide a comparative proteomic evaluation of TOs and primary tumours, revealing both shared and distinct molecular signatures.

Correlating TO treatment responses with clinical outcomes typically requires large cohorts for normalization. To address this, we developed a pipeline that contextualizes IC50 Z scores using publicly available pharmacogenomic data, enabling scalable response analysis in small patient-derived TO sets. Although organoids were primarily derived from treatment-naive surgical specimens, prior studies suggest that such material retains predictive value for post-treatment interventions35. While HO are valuable for assessing CAR T cell specificity, they are not suitable as controls for chemotherapy testing. CAR T cell therapy in solid tumours is challenged by limited efficacy and the risk of severe on-target, off-tumour toxicities4. To address this, we developed a patient-derived coculture platform using TOs and matched HOs to simultaneously assess CAR T cell cytotoxicity and tissue specificity. By combining IHC-based antigen profiling with functional killing assays, our model enables individualized evaluation of therapeutic potential and safety, supporting the refinement of CAR T cell strategies for lung cancer. Although most organoids reflected TAA expression patterns of their parental tumours, discrepancies such as cMET overexpression in culture emphasize the need to validate antigen profiles before functional testing. Our model incorporates TAA profiling, cytokine secretion and resistance-associated proteomic features that might influence CAR T cell performance. Notably, we observed that CAR T cell activation does not always lead to efficient killing at physiological E:T ratios. While high E:T ratios result in killing of both TOs and HOs, lower ratios, more representative of in vivo conditions, require serial killing and reveal differential cytotoxicity linked to tumour-specific factors, providing a more accurate assessment of therapeutic selectivity.

TO9 exemplifies a robust responder to HER2-28z CAR T cells. Its heightened susceptibility is probably attributable to high HER2 expression, limited PDL1 upregulation, low IL-8 secretion and a proteomic profile lacking autophagy- and immune-evasion-associated proteins previously linked to CAR T cell resistance32,33. These factors collectively underscore the multifactorial determinants of CAR T cell efficacy. This observation aligns with reports that HER2 CAR sensitivity to the PD1–PDL1 axis is modulated by CAR affinity36, probably reflecting stronger immune synapse formation in the context of high antigen density, such as in TO9. TO9’s molecular profile therefore identifies it as a promising candidate for HER2-targeted CAR T cell therapy. By contrast, TO12 exhibited strong CAR T-cell-mediated killing despite low HER2 expression, an outcome not predicted by antigen profiling alone. Mechanistically, TO12 secreted IL-6 (a pro-inflammatory cytokine known to enhance CAR T cell activity37), which closely mirrored expression in the parental tumour, reinforcing model fidelity. This cytokine milieu may have supported CAR function even in the absence of high target density. Notably, TO12 also responded to PD-L1-28z CAR T cells, despite the generally lower cytokine production observed with this CAR. IL-6 secretion may have compensated for suboptimal CAR activation, enabling tumour cell killing. Thus, IL-6-rich tumours may represent favourable candidates for CAR T cell therapy, potentially due to a pro-inflammatory microenvironment that supports T cell activation.

Prior studies using homogeneous cell line models have reported correlations between CAR T cell efficacy and antigen density38. While such relationships appear more consistent in haematological malignancies, where TAAs are typically well defined and highly expressed39,40, this paradigm does not fully extend to solid tumours, where TAA expression is often heterogeneous and antigen selection remains a therapeutic challenge. Using our TO model, we observed a positive but non-definitive association between HER2 or PDL1 expression and CAR T-cell-mediated killing, emphasizing that antigen density is an informative but not sufficient predictor of CAR T cell efficacy in lung cancer. Together, our findings highlight that CAR T cell responses in lung tumours are shaped by a complex interplay of antigen abundance, cytokine signalling and resistance-associated molecular features, reinforcing the need for patient-specific functional testing to complement conventional biomarker-driven approaches.

Our inclusion of matched HOs provides an essential tissue-specific control for detecting on-target, off-tumour effects, a critical consideration for targets like HER2, where safety concerns have constrained clinical development41. Notably, several tumours in our cohort would meet current inclusion criteria for HER2-targeted trials based on expression alone, yet only a subset showed functional sensitivity. This disparity underscores the value of incorporating functional testing to refine patient selection and mitigate clinical risk in CAR T cell therapy. To further demonstrate clinical feasibility of our platform, we established and tested matched TOs and HOs from patients 27 and 32 within 3 months of surgery. In patient 27, HER2-28z and PDL1-28z CAR T cells induced selective killing of TOs, confirming the utility and translatability of our approach for prospective clinical testing.

In summary, our findings establish patient-derived lung TOs as a high-resolution, physiologically relevant model for evaluating CAR T cell efficacy and resistance in a patient-specific setting. Integration of optimized coculture systems, live-cell imaging, phenotypic characterization and cytokine profiling enables identification of TOs with selective CAR T-cell-mediated killing and facilitates dissection of resistance mechanisms. Together, these features support the evaluation of precision CAR T cell therapy in lung cancer and may inform personalized treatment strategies, including checkpoint blockade and logic-gated CARs for lung cancer. Future technological developments could further increase the predictive and translational value of our platform. Incorporating stromal and immune components into microfluidic or perfused organoid systems may enable more accurate modelling of CAR T cell trafficking, persistence and immunomodulation. Coupling these models with high-content imaging and single-cell multiomics could reveal spatial and molecular dynamics of tumour–T cell interactions in real time. The same workflow can be readily adapted to other solid tumours such as breast, pancreatic or colorectal cancer, enabling cross-indication benchmarking of CAR designs. Collectively, these advances will broaden the applicability of patient-derived TOs as a versatile preclinical platform for rational and personalized development of next-generation cell therapies.

Patient samples

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Patients undergoing surgery of a histologically proven lung tumour at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin were consecutively recruited without preselection. Given the consecutive recruitment and exploratory nature of the study, no systematic selection bias is expected. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Charité (EA2/274/20). Cross-sectional slices of tumour tissue were obtained by a pathologist, along with macroscopically inconspicuous HT taken as far as possible from the tumour site. Transport of tissue and blood was performed on ice in HBSS (Gibco, 14175053), supplemented with penicillin–streptomycin (100 U ml−1 and 100 µg ml−1; Gibco, 15140-122). Samples were either directly processed for organoid culture or frozen. Tissue was washed in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (Gibco, 41966-029) containing 5% foetal calf serum (FCS; Sigma, F7524), penicillin–streptomycin, 10 mM HEPES (Gibco, 15630049) and Amphotericin B (2.5 µg ml−1; Bio&Sell BS.A 2612 or Gibco 15290026), cut into pieces and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. For cryopreservation of viable cells, 500 µl FCS per 500 mg tissue and 500 µl 2× freezing medium (80% FCS, 20% dimethyl sulfoxide; AppliChem A3672,0100) were added; samples were slowly cooled to –80 °C and transferred to liquid nitrogen. Peripheral blood for CAR T cell generation was obtained from healthy humans (Ethics Committee of the Charité approval EA4/091/19).

Organoid culture

Organoid cultures were established from primary human lung tumour or heathy tissue. Donor sex and relevant clinical information are provided in Supplementary Table 1. If immediately processed, the healthy or tumour specimen was covered in wash buffer in a Petri dish and mechanically dissociated into small fragments using a sterile blade and forceps. If organoid culture was initiated from frozen specimens, the tissue was rapidly thawed, transferred into a 50-ml Falcon tube containing 20 ml wash buffer and centrifuged at 400g for 3 min at 4 °C. Tumour tissue was dissociated in 5 ml DNase medium (wash buffer supplemented with 50 µg ml−1 DNase I (Roche, 101041599001) and 10 µM ROCK inhibitor (Selleckchem, S1049)) per 1 mg of tissue using a gentleMACS dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec). Lung tissue was digested in 5 ml digestion medium (wash buffer, 1 mg ml−1 Collagenase D (Roche, 11088858001), 100 µg ml−1 DNAse I, 5 U ml−1 Dispase and 10 µM ROCK inhibitor) per 1 mg tissue using a gentleMACS dissociator. Tumour tissue was pressed through a 100-µm pluriStainer (pluriSelect). Lung tissue was pushed carefully through the 100-µm pluriStainer. This was repeated using a 70-µm pluriStainer (pluriSelect). If necessary, tissue incubated with 5 ml RBC lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher, 00-4333-57) and washed between the filtering steps. After centrifuging 400g for 5 min at 4 °C, the cell pellet was resuspended in 5 ml wash buffer. For debris-rich tumour samples, the Dead Cell Removal Kit (130-090-101, Miltenyi Biotec) was applied. Cells were counted using a Neubauer chamber. Cells were seeded at 5000 cells µl−1 Geltrex (Thermo Fisher, A1413202). Domes (20 µl or 50 µl Geltrex) were seeded in preheated 48-well plates (Greiner, 677102) or 24-well plates (TPP, 92424), respectively. After incubation for 30 min at 37 °C, organoid medium was added (200 µl per 48-well or 500 µl per 24-well). Basal medium contained Advanced Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium/F-12 (Thermo Fisher, 12634010), 100 units ml−1 penicillin and 100 µg ml−1 streptomycin (Gibco, 15140-122), 2.5 µg ml−1 Amphotericin B, 10 mM, 1% HEPES, 1× B27 (Thermo Fisher, 17504044), 10 mM nicotinamide (Sigma, N0636,), 1 mM N-acetyl-L-cysteine (Sigma, A9165) and 1 µM A83-01 (Tocris, 2939). GlutaMAX (8 mM for TO medium, 2 mM for HO medium; Gibco, 35050061) and SB202190 (1 µM for TO medium, 0.5 µM for HO medium; Cayman Chemical, 10010399), EGF (50 ng ml−1, only at initiation for HOs; Sigma, E9644) were added. In addition, medium formulations comprised 25 ng ml−1 FGF7 (PeproTech, 100-19), 100 ng ml−1 FGF10 (PeproTech, 100-26), 10% RSPO1-conditioned medium (CM) and 100 ng ml−1 Noggin (PeproTech, 120-10C) (only HOs); or 25 ng ml−1 FGF7, 100 ng ml−1 FGF10, 50% WNT, RSPO1, Noggin (WRN) CM. If indicated, 3 µM CHIR99021 (Sigma, SML1046) was added. FGF2-containing medium included basal medium + 20 ng ml−1 FGF2 (PeproTech, 100-18B) and 50% WRN CM. In all media, 10 µM ROCK Inhibitor was added for culture initiation or passaging. WRN CM was derived from L-WRN cells as described previously42. RSPO1 CM was derived from Cultrex HA-R-Spondin1-Fc-293T Cells (R&D, 3710-001-01). Cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Medium was changed every 3–4 days with daily microscopy. The organoids were detached when they occupied more than 75% of the organoid–Geltrex dome. Domes were washed with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS), incubated in TrypLE Express (Gibco, 126013; 10 min, 37 °C), washed with cold DPBS, centrifuged, resuspended in Geltrex, reseeded, polymerized 30 min at 37 °C and overlaid with medium. Splitting ratios ranged from 1:1.5 to 1:4.

DNA sequencing and DNA methylation assay

DNA from fresh and frozen healthy and tumour tissue and organoid cells was extracted with Quick-DNA Miniprep Plus Kit (Zymo Research, D4068) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA purity and concentration were examined by spectrophotometry and fluorometry.

DNA sequencing

DNA fragmentation was performed enzymatically or by physical shearing for samples with DNA <14 ng µl−1. A targeted DNA sequencing panel for lung cancer-associated mutations covering 500 kb was designed (Supplementary Table 2a). Mutations were selected on the basis of abundance in the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) database. Ten single-nucleotide polymorphisms for genomic fingerprinting were added. Furthermore, a custom panel of 39 genes was also used (Supplementary Table 2b). DNA library preparation was performed using Magnis NGS Prep System (Agilent). Library concentration and quality was assessed using Fragment Analyzer 5200 (Agilent). DNA sequencing was carried out on the MiniSeq (Illumina) or NovaSeq (Illumina) platform. The targeted sequencing panel achieved 200× coverage, and WES achieved 150× coverage.

DNA methylation assay

Organoids cultured for 3 (short-term), 6 (mid-term) and 9 (long-term) months were included. DNA was subjected to bisulfite conversion using the EZ DNA Methylation-Gold Kit (Zymo Research). DNA methylation levels were analysed using the Infinium MethylationEPIC Kit (Illumina EPIC-8 BeadChip, Illumina). Imaging was performed using the iScan Microarray Scanner (Illumina).

Histology

After fixation for 24 h in 4% formaldehyde, primary tissue samples were embedded in paraffin and cut into 4-μm sections. Geltrex-embedded organoids were embedded in Histogel (Thermo Fisher, 1200667) and fixed overnight in 4% formaldehyde. Paraffin sections were deparaffinized by standard methods. Sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin, 1% periodic acid and Schiff´s reagent. For IHC, antigen retrieval was performed in CC1 mild buffer (Ventana Medical Systems) for 30 min at 100 °C or in protease 1 for 8 min. Sections were stained for TTF1 (1:100, Zytomed), CK5/6 (1:100, Epitomics), CK7 (1:1000, Dako), p40 (Ventana Medical Systems), p63 (1:25, Leica), PDL1 (1:200, Cell Signaling), HER2 (Ventana Medical Systems), CEA (1:4000, Dako), MSLN (1:10, Thermo Fisher), MUC1 (1:100, Dako), ALK (Ventana Medical Systems), cMET (Ventana Medical Systems) and CD56 (1:50, Leica) for 60 min at room temperature and visualized using the avidin–biotin complex method and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine. IHC was performed on a BenchMark XT immunostainer (Ventana) with haematoxylin and bluing reagent counterstaining. Slides were assessed using Leica Confocal TCS SP8 microscope and Leica Application Suite X 3.5.7.23225 imaging software. Tumour content was evaluated by haematoxylin and eosin staining (tumour cells/total cells), and cell type annotation was performed.

IHC analysis—H-score semi-quantification

Whole-slide imaging of IHC sections was performed with Axio Scan Z.1 (Zeiss). Protein expression was semi-quantitatively assessed by H-score (0–300, based on percentages of cells at four intensity levels). Image analysis used QuPath (0.6.0-rc4) with marker-specific pipelines:

TO/HO: Organoid regions were segmented by haematoxylin optical density classifier; positive cells were quantified with predefined 3,3′-diaminobenzidine thresholds (low/medium/strong, marker specific). If multiple passages were analysed, mean H-scores were reported. ALK H-scores were manually evaluated by a pathologist.

TT: Tumour regions were manually annotated, a custom classifier identified tumour cells, and H-scores were calculated with the same thresholds.

HT: Bronchial epithelial regions were manually annotated, and H-scores were calculated with the same thresholds.

LC–MS

Protein extraction from tissue and organoid samples, digestion and peptide desalting were carried out using the filter-aided sample preparation technique43. Peptides were separated by LC–MS using a C18 column (Acclaim PepMap RSLC, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and detected with a timsTOF HT flex mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics). Data-independent acquisition with parallel accumulation–serial fragmentation was performed: PASEF18 mode with ten PASEF MS/MS scans. Capillary voltage was set to 1,600 V, and spectra were recorded over an m/z range of 100–1,700 with an ion mobility range (1/K0) of 0.85–1.30 Vs cm−2. Collision energy was ramped linearly from 59 eV at 1/K0 = 1.6 Vs cm−2 to 20 eV at 1/K0 = 0.6 Vs cm−2. Precursors with charge state 0–5 were selected (target 20,000; intensity threshold 2500). Raw data were processed using DIA-NN (DIA-NN 1.8.2). For the library-free search, an in silico digest of 20,368 human protein entries from UniProt was used with deep-learning-based spectra, retention time and ion mobility prediction.

IL-6 immunoassay

Tissue specimens were disrupted with a BeadBlaster homogenizer (Biozym Scientific) in T-PER reagent (Thermo Scientific, 78510). IL-6 concentrations were measured in lysates by Luminex immunoassay (Merck) on a Bio-Plex 200 System (Bio-Rad). Cytokine levels were calculated from fluorescence intensity using manufacturer standards after background subtraction. Data were normalized to 0.01 g wet weight.

Cytotoxicity assay in TOs and tumour cell line controls

TOs were incubated with StemPro Accutase (Gibco, A1110501) and 50 µg ml−1 DNAse I at 37 °C until a single-cell suspension formed. After washing with DPBS, cells were seeded in a 384-well microplate (Greiner Bio-One, 781096) with 4,000 cells per well in 20 µl Geltrex. After 15 min at 37 °C, 20 µl medium supplemented with 10 µM ROCK inhibitor was added. NCI-H292 (American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) CRL-1848) and A549 (ATCC CCL-185) tumour cell lines were used as controls. Cell lines were authenticated by the vendor (ATCC) using short tandem repeat profiling, and confirmed not to appear in the International Cell Line Authentication Committee database of misidentified cell lines. They tested negative for mycoplasma and were not cultured beyond passage 30 to ensure cell identity and avoid cross-contamination. Cell lines were digested with TrypLE Express (Gibco) at 37 °C until single-cell suspensions formed and were seeded analogously. TOs and cell lines were grown for 2 days before chemotherapeutics were added in 20 µl medium containing NucRed Dead 647 (1:5 dilution; Thermo Fisher, R37113) to label live/dead cells. Viability was monitored by Opera Phenix High Content Screener (Revvity) and endpoint at day 5 measured by CellTiter-Glo Assay (Promega, G7571) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The luminescence was measured with SpectraMax iD5 (Molecular Devices).

Modular CAR library

A pUC19 vector encoding a CD19-28z CAR (Addgene, #183473) homology-directed repair template (HDRT) with homology arms targeting the TRAC locus was used31. The plasmid was linearized by PCR excising the scFv region using flanking primers and incubated for 15 min at 50 °C with the new scFv gene block (Integrated DNA Technologies, IDT) at 1:3 ratio in In-Fusion cloning mix (Takara). Two microlitres of the reaction were transformed into Stellar Competent Escherichia coli and positively selected by ampicillin Luria-Bertani agar plates. Plasmids were purified with ZymoPURE Miniprep Kit (Zymo Research) and validated by Sanger sequencing (LGC Genomics). CAR HDRTs were PCR-amplified as previously described31. CAR sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 8.

CAR T cell generation

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated using standard density gradient centrifugation. Purified peripheral blood mononuclear cells were positively enriched for CD3+ T lymphocytes using anti-CD3 magnetic microbeads (CD3 MACS, Miltenyi Biotec). Enriched T cells were activated for 48 h in cytotoxic T lymphocyte medium (Advanced RPMI and Clicks Medium mixed at 1:1) supplemented with 10% FCS, 1% GlutaMAX (Gibco), IL-7 (10 ng ml−1, 1410-050 CellGenix) and IL-15 (10 ng ml−1, 1413-050 CellGenix) in a 24-well plate precoated with 1 µg ml−1 CD28 (302934, BioLegend) and 1 µg ml−1 CD3 (16-0037-85, Invitrogen). After 48 h, T cells were collected, centrifuged (10 min, 350g, room temperature), washed once with MaxCyte buffer and resuspended at 200 × 106 cells ml−1. Ribonucleoprotein complexes (RNPs) were produced by mixing sgRNA and Cas9 in the presence of polyglutamic acid (Sigma-Aldrich). Polyglutamic acid (0.33 μl, 100 μg μl−1 stock) was mixed with TRAC-targeting sgRNA (5′ GGGAATCAAAATCGGTGAAT 3′; 0.32 μl, 100 μM stock, IDT) and Alt-R S.p. Cas9 Nuclease V3 (0.267 μl, 10 μg μl−1 stock, IDT) was added (sgRNA:Cas9 molar ratio 2:1). The RNP mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 15 min and used for electroporation. RNP and HDRTs (at a final concentration of 35 nM) were mixed and combined with 20 µl of cell suspension, transferred to MaxCyte OC-25×3 processing assemblies and electroporated with pulse code ‘Expanded T cell 4-2’ in the MaxCyte GTx (Maxcyte). After electroporation, cells were allowed to rest, the medium was exchanged, and the cells were subsequently cultured and expanded. Once expansion reached day 12 post isolation, CAR T cells were purified by MycTag staining (AF647 antibody, Cell Signaling, 2233; 30 min, 4 °C, dark) and enriched with anti-AF647 magnetic microbeads per the manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-091-395). Enriched cells were cultured at 1.5 × 106 cells ml−1, allowed to rest for 2 days and then used for assays.

Flow cytometry analysis

All antibodies used were manufactured by BioLegend, unless stated otherwise, and titrated beforehand. Flow cytometry data were acquired on a Cytoflex LX (Beckman Coulter) and analysed with FlowJo v.10.8.0 (BD Biosciences).

Immunophenotyping of tissue and organoids

Lung tissue and tumour tissue processed for culture initiation or organoids and TOs after dissociation into single cells were incubated for 15 min with Human TruStain FcX (BioLegend). Cells were stained for 20 min at 4 °C in the dark using anti-human fluorophore-conjugated antibodies against PDGFRa-APC (16A1), CD45-FITC (HI30), CD31-PerCP-Cy5.5 (WM59), EpCAM-PE (9C4), CD133-PE/Cy7 (clone 7), CD166-APC/Fire750 (3A6) and CD44-BV650 (IM7). LIVE/DEAD Fixable Blue Dead Cell Stain (ThermoFisher) was used to exclude dead cells.

Knock-in efficiency

The phenotype and knock-in efficiency of CAR T cells were assessed by a mastermix of anti-human fluorophore-conjugated antibodies containing CD8-BV510 (RPA-T8), CD3-BV650 (OKT3), CCR7-AF488 (G043H7), CD4-PerCP-Cy5.5 (SK3), CD45RA-PECy7 (HI100) and MycTag-AF647 (9B11, Cell Signaling Technology). DAPI (2.5 μg ml−1) was used to exclude dead cells. Cells were collected and washed once with fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer (phosphate-buffered saline supplemented with 0.5% bovine serum albumin and 2 mM EDTA). Centrifugation was at 350g, 5 min, 4 °C. Cells were stained with antibody mastermix in FACS buffer for 30 min at 4 °C in the dark, washed once and resuspended in 100 µl FACS buffer in 96-well U-bottom plates (Falcon) for acquisition.

CAR T cell activation and cytokine production

Bulk CAR T cells were cocultured for 12–16 h with TOs or organoids in a 96-well U-bottom plate at an E:T ratio of 1:1. Intracellular cytokine production was captured by addition of 2 μg ml−1 of Brefeldin A (Sigma-Aldrich) after 1 h of stimulation and cells were stained using antibodies and the FoxP3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (eBioscience). The following antibodies were used: CD3-BV650 (OKT3), CD4-PerCP-Cy5.5 (SK3), CD8-BV510 (RPA-T8), IFN-γ-BV605 (4S.B3), TNF-AF700 (MAb11), IL-2-PECy7 (MQ1-17H12), CD137-PE (4B4-1), CD154-BV421 (24–31), CCR7-APC-F750 (G043H7), CD45RA-PEDazzle (HI100) and Myc-Tag-AF647 (9B11, Cell Signaling). LIVE/DEAD Fixable Blue Dead Cell Stain (L/D; ThermoFisher) was used to exclude dead cells.

PDL1 and EGFRvIII quantification on organoids

Organoids and TOs were incubated with StemPro Accutase and 50 µg ml−1 DNAse I at 37 °C until single-cell suspensions formed. They were washed twice with FACS buffer and incubated for 15 min with Human TruStain FcX (BioLegend). Subsequently, the cells were stained for 15 min at 4 °C in the dark with either anti-human PD-L1-PE (29E.2A3), anti-human EGFRvIII-PE (DH8.3.Rec) or the corresponding mouse isotype controls IgG2b, κ-PE (27-35) or IgG1, κ-PE (MOPC-21). DAPI was added at 2.5 μg ml−1 before measurement. Cells were analysed with Quantibrite beads (340495, BD Biosciences) to determine molecules per cell, calculated per the manufacturer’s instructions and normalized to isotype controls.

Organoid killing assay

Single organoid cells from 7-day EGF-omitted cultures were seeded at 6,000 cells per well in 384-well flat-bottom imaging plates (781096, Greiner Bio-One) with 20 µl organoid medium and 1% Geltrex plus ROCK inhibitor (10 μM). Cells were cultured for 72 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2 until organoids formed. On the day of the assay, CAR T cells were labelled with Cell Proliferation Dye eFluor 450 (1:2,000; Thermo Fisher) and resuspended in 20 µl cytotoxic T lymphocytes medium (Advanced RPMI and Clicks Medium mixed at 1:1 supplemented with 1% GlutaMAX) with 10% FCS and NucRed Dead 647 (1:10; Thermo Fisher) to label live/dead cells. CAR T cells were added to TOs or HOs at E:T ratios of 5:1, 1:1 or 1:5. Plates were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C and imaged every 3 h for up to 30 h with an Opera Phenix High Content Screener (Revvity) with an incubation chamber (37 °C, 5% CO2) using a 10× objective. Supernatants were collected at the endpoint for cytokine analysis.

Cytokine analysis

Twenty microlitres of supernatants were collected from killing assays, transferred to 96-well U-bottom plates and centrifuged at 1,000g for 5 min. Fifteen microlitres of cleared supernatant were snap-frozen at –80 °C, thawed and analysed with the V-Plex Pro-inflammatory Panel 1 Human Kit (K15049D, MesoScaleDiscovery) for IFNγ, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-13 and TNF. Measurements were performed on a MESO QuickPlex SQ 120MM with support from CheckImmune GmbH.

Statistics and reproducibility

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. Sample sizes were chosen empirically on the basis of assay feasibility and consistency observed in preliminary optimization experiments. Each experiment was independently repeated at least three times with technical and biological replicates, which proved sufficient to ensure reproducibility of the findings. Blinding was not applicable, as all experiments were performed in vitro using predefined experimental conditions and quantitative readouts.

DNA sequencing

Complex heatmap (v.2.22.0), circlize (v.0.4.16) and gridExtra (v.2.3) packages in R were used to create mutation plot and heatmaps. The geom_smooth (method = ‘lm’) command in the ggplot2 (v.3.5.1) package was used to fit a linear model to mean VAF comparison between TTs and TOs. To evaluate determinants of culture success, the Mann–Whitney test and a simple logistic regression model were applied using Prism (GraphPad) v.10.2.3. A two-tailed P value was used to determine the significance level44,45.

DNA methylation data

Data were preprocessed and normalized using the minfi package (v.1.46.0) with standard filtering applied. DMPs were identified using the limma package (v.3.56.2). For visualization, donor effects were adjusted using the Combat function from the sva package (v.3.52.0)46,47,48.

Proteomics

Analyses were performed using R. Missing values were imputed using QFeatures (v.1.16.0). VennDiagram package (v.1.7.3) was used to generate Venn diagrams. Gene Ontology pathway enrichment analysis of protein lists was performed using the clusterProfiler package (v.4.14.4) in conjunction with org.Hs.eg.db (v.3.20.0) and AnnotationDbi (v.1.68.0) packages. The UpSetR package (v.1.4.0) was used for visualization. Datasets were filtered and principal component analysis (PCA) performed for dimensionality reduction. The umap package (v.0.2.10.0) was used for UMAP analysis. Ranked protein lists were subjected to pathway enrichment analysis for HO and HT conditions using the ReactomePA package (v.1.50.0). The limma (v.3.62.2) package was used to perform the differential expression analysis, and the EnhancedVolcano (v.1.24.0) package was applied for plotting. Cut-off values for differentially expressed proteins were set at a log2 fold change of ±0.5 and an adjusted P value of ≤0.005. Proteins above the log fold change threshold were retrieved, and enriched pathways were analysed using Hallmark gene sets from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) using the GSEABase (v.1.68.0) package. Pathways associated with the top 20 mutations in WES or targeted DNA sequencing data were identified using the pathway browser at https://reactome.org. Pathway enrichment analysis was performed using the Reactome GSA (v.1.20.0) package, single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) was used as analysis method, interactors were used and disease pathways were included in the request49. Euclidean distance and ward.D2 linkage were applied for clustering. Autophagy-related subsets were selected using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway database, and immune-evasion genes were extracted from the MSigDB by using the Msigdbr (v.7.5.1) R package (Supplementary Table 5).

H-score and IL-6 Luminex analysis

Analysis of H-scores was performed in R using readxl (v.1.4.3), dplyr_(v.1.1.4), stringr_(v.1.5.1), tibble (v.3.2.1) ComplexHeatmap (v.2.22.0) and viridis_(v.0.6.5) packages; for plotting IL-6 Luminex results, the ggplot2 (v.3.5.2) package was used.

Cytotoxicity assay

For the analysis of CellTiter-Glo, fluorescent units were normalized to the largest (100%) and smallest (0%) mean in each dataset and the 0.15625% DSMO control. Nonlinear regression (curve fit) was performed using the log (inhibitor) versus normalized response equation in Prism (GraphPad) v.10.2.3. IC50 values for each chemotherapeutic agent were normalized independently, then drug activity scores (1/IC50) were calculated and normalized to Z scores (of drug activity) for each drug dataset. Further analyses were performed using the rcellminer (v.2.28.0) package in R; drugs with multiple entries in the Cellminer database were summarized by weighting the number of experiments conducted to generate a single Z score\((\frac{({Z}_{1}\times {\mathrm{EXP}}_{1})\,+\,({Z}_{2}\times {\mathrm{EXP}}_{2})}{{\mathrm{EXP}}_{1}\,+{\mathrm{EXP}}_{2}})\). Experimental data were integrated with the Cellminer database using A549 as the reference, with appropriate scaling factors applied. Scaled Z scores were plotted together with lung cancer cell lines from the Cellminer database to identify thresholds of drug activity resistance or sensitivity50.

Imaging analysis

Imaging analysis was performed with signalsImageArtist (Revvity) following the provided building blocks (Supplementary Table 8) to identify intact organoid and subtract dead cells to quantify viable organoid area. Viable area of intact organoids was assessed over time to calculate killing percentages following the equation \(\mathrm{Killing}\,\mathrm{percentage}=100-(\frac{\mathrm{Timepoint}\,\mathrm{viable}\,\mathrm{area}}{\mathrm{Initial}\,\mathrm{viable}\,\mathrm{area}}\times 100)\). Specific killing was calculated by subtracting the positive killing percentage from an irrelevant control CAR (CD19-28z) from tested CARs (HER2-28z, PDL1-28z and EGFRvIII) at each timepoint.

Correlation and linearity analyses

We assessed the relationship between antigen expression and CAR T cell cytotoxicity using R software and the following packages: psych (v.2.5.6), corrplot (v.0.95), ggplot2 (v.3.5.2), Hmisc (v.5.2-3) and ggpubr (v.0.6.0). Data distribution was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Spearman correlation and linear regression were performed to assess associations with two-sided P values.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Rate this article

Login to rate this article

Comments

Please login to comment

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!