Space & Astronomy

10 min read

Is There Always Liquid Water on Ice? Unraveling the Mystery

AIP Publishing LLC

January 20, 2026•2 days ago

AI-Generated SummaryAuto-generated

New research bridges physics theories to resolve controversy surrounding a thin liquid layer on ice. Computer simulations suggest this "premelting film" exists at the ice-water equilibrium point, but experiments often occur slightly away, leading to conflicting observations of its thickness. This phenomenon influences ice crystal growth and has potential applications in atmospheric physics and friction science.

Bridging theories across physics helps reconcile controversy about the thin liquid layer on icy surfaces.

From the Journal: The Journal of Chemical Physics

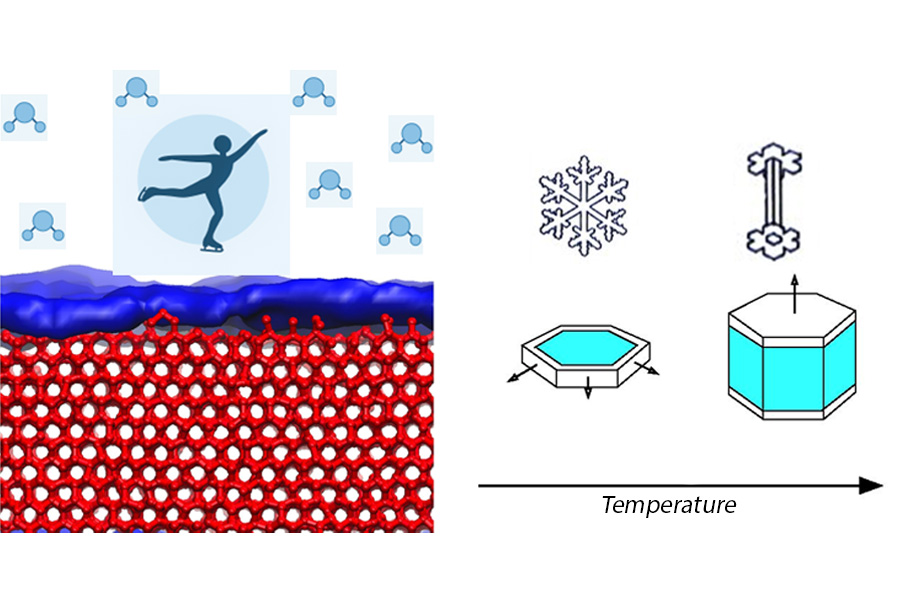

WASHINGTON, Jan. 20, 2026 — The ice in your freezer is remarkably different from the single crystals that form in snow clouds, or even those formed on a frozen pond. As temperatures drop, ice crystals can grow in a variety of shapes: from stocky hexagonal prisms to flat plates, to Grecian columns.

Why this structural roller coaster happens, though, is a mystery. When first observed, researchers thought it must relate to a hypothesis proposed by famed physicist Michael Faraday — ice below its melting point has a microscopically thin liquid layer of water across its surface.

This “premelting film” of ice, however, is the subject of significant scientific controversy. For years, researchers have provided contradictory evidence about its thickness and whether it even exists.

In The Journal of Chemical Physics, by AIP Publishing, Luis MacDowell from Universidad Complutense de Madrid sought to resolve this contention.

MacDowell focused on the phase diagram of ice — a representation of how ice, liquid water, and vapor exist across temperatures and pressures. In it, there is one minuscule dot, called the triple point, where all three phases are equally stable and coexist in perfect equilibrium.

Using computer simulations, MacDowell visualized the movements of molecules at the surface of ice. At the triple point, a nanometer-thin film appeared. Yet, many experiments reported a much thicker film. MacDowell proposed that much of the disagreement about the thin water layer is due to experiments that unintentionally occur slightly away from equilibrium.

“Equilibrium is a point,” he said. “You are as close as you can be, but never just there. Just a tiny deviation can become sufficiently out of equilibrium, making it very difficult to measure these things.”

The liquid film is restricted to a limited thickness near this equilibrium point because of water’s unusual density properties, with solid ice being an energetically preferable state over liquid water.

Combining theories across physics disciplines, MacDowell explained observations of liquid droplets condensing atop the film, presenting partial wetting, and theorized why ice crystals grow the strange way they do.

“This sequence of transitions in the shape of the snow crystals is related to changes in premelting film thickness that occur at the surface of ice,” MacDowell said. “It exhibits surface phase transitions, and at each transition, you have a sudden change of the properties and of the growth rate of the faces.”

Because the face and the sides grow at distinct rates, different crystal shapes emerge. MacDowell hopes his theories can be applied to atmospheric physics and to friction science and even help to understand how ice skating works.

Still, the problem is not entirely solved. MacDowell plans to investigate how friction influences the slipperiness of ice and how impurities affect the film thickness.

###

Article Title

The key physics of ice premelting

Authors

Luis G. MacDowell

Author Affiliations

Universidad Complutense de Madrid

Rate this article

Login to rate this article

Comments

Please login to comment

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!