Geopolitics

19 min read

Beyond Earthquakes: The Biggest Tsunamis Were Caused by Landslides

Earth.com

January 18, 2026•4 days ago

AI-Generated SummaryAuto-generated

The largest historical tsunamis were caused by landslides, not earthquakes. New global evidence reveals these events can generate exceptionally high waves, particularly in narrow fjords and reservoirs, leaving little time for reaction. The highest recorded wave, at Lituya Bay, Alaska, resulted from a landslide. This finding highlights a critical forecasting challenge as landslide waves can strike sooner than earthquake-generated ones.

Some of the most destructive tsunami waves in history do not come from the ground shaking, but from landslides collapsing down mountains into water without warning.

New global evidence shows these events can raise walls of water far higher than most earthquake-driven tsunamis, often striking places with little time to react.

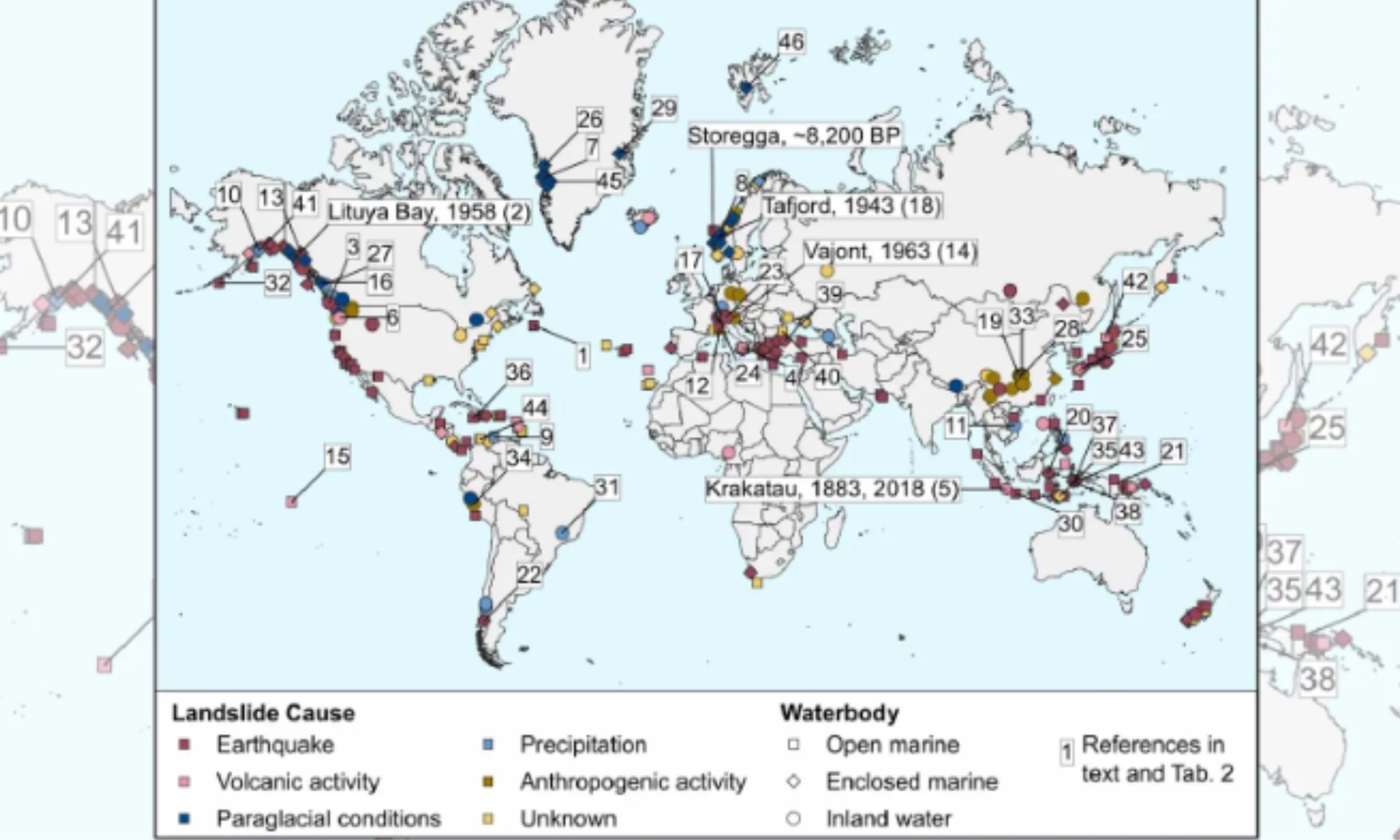

The finding comes from a global catalog that examined 317 documented tsunamis triggered by landslides, tracing where the highest waves occurred across fjords, coastal inlets, and inland reservoirs.

A landslide-triggered tsunami, a wave made when moving ground shoves water aside, begins where the slide meets the water.

The work was led by Katrin Dohmen at Technische Universität Berlin (TU Berlin), where she studies coastal hazards. Her team compared locations, triggers, and wave heights, which clarifies how basin shape controls final wave height.

History of landslide tsunamis

Narrow fjords, small bays, and reservoirs can produce extreme wave heights because the water has nowhere broad to spread.

In enclosed marine environments, basins that trap waves between close shores, energy stays trapped and the crest grows higher near people.

The same geography also limits long-distance travel, so the worst heights can fade quickly once a wave exits the basin.

Field teams often measure a tsunami by the stains and broken vegetation it leaves on slopes and buildings.

Scientists call the highest mark run-up, the highest point water reaches on land, because it captures inland reach.

Using run-up and nearshore water height can reduce confusion, but missing measurements still make many old events hard to compare.

The record everyone cites

In 1958, a landslide into Lituya Bay, Alaska, drove run-up to about 1,720 feet, the highest ever recorded for a wave event.

The sliding rock hit the narrow inlet and displaced water upward in seconds, which stripped trees from a hillside and left a clear trimline still visible today.

About 7.5 miles away at the bay mouth, the wave was nearer 30 feet, showing fast decay as energy spread, water depth increased, and the surge moved out of the confined basin.

When earthquakes trigger tsunamis

Ground shaking can knock loose coastal cliffs and underwater sediment, creating a wave on top of the tsunami that the quake itself starts.

The catalog shows earthquakes and volcanic collapses drive the greatest losses, yet the biggest waves usually need a slide in tight terrain.

This creates a forecasting problem, because an earthquake warning may miss a nearby landslide wave that arrives sooner than expected.

Unstable volcanic slopes can fail without much notice, sending rock and ash into the sea in minutes.

When that moving mass enters water, its momentum pushes the surface upward, and the first surge can hit nearby shores quickly.

Because eruptions and collapses can overlap, emergency plans near island volcanoes must treat sudden waves as a separate risk.

Ice melt and landslide tsunamis

Glacier loss can leave steep rock faces unsupported, and cracks widen as ice that once held them in place thins.

Researchers call this paraglacial conditions, the landscape adjustment after glacier retreat, and it can prime slopes for collapse.

In 2023, a Greenland rockslide produced a 656-foot tsunami and a nine-day water oscillation that reverberated through a confined fjord, repeatedly sloshing water back and forth long after the initial impact.

Rain can weaken slopes

Heavy rain soaks soil and fractured rock, and extra water weight increases the chance that a hillside starts sliding.

Rising pore water pressure, water pressure inside soil that reduces friction, can let gravity overcome the slope’s strength.

In narrow valleys and river reservoirs, that process can turn a storm into a sudden wave that leaves little time to move.

Humans can trigger waves

Reservoir drawdowns and refilling can stress nearby slopes, because changing water levels also change groundwater levels in the banks.

As the bank drains or saturates, uneven water pressure can open cracks and reduce friction along weak layers, and a slide follows.

The catalog links the highest inland-water waves to such human choices, which matters for dam operators.

Many offshore landslides leave no surface scar, so scientists must look for seafloor clues rather than eyewitness reports.

High-resolution bathymetry, maps of underwater depth and shape, can reveal fresh slump blocks and tracks that low detail misses.

The common public basemap, the General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO), is often too coarse for small failures.

Why resolution matters here

Most tsunami-causing submarine slides are smaller than about 0.24 cubic miles, so a coarse grid can smooth them away.

GEBCO uses a 15 arc-second spacing, about 1,500 feet at the equator, so many slide scars. Finer surveys go beyond GEBCO and feed susceptibility mapping, maps that rank likely failure sites, but many coasts still lack coverage.

Warning time can be seconds

Nearshore landslide waves can reach the closest beach in under two minutes, because the source sits right offshore or above it.

Nearshore landslide waves can reach the closest beach in under two minutes, leaving officials almost no time to issue a warning.

The best chance comes when an unstable slope is already known, so sensors can trigger alerts before movement becomes fast.

Tracking landslide tsunamis

In the open ocean, seafloor pressure sensors can detect passing tsunamis even when coastal gauges stay quiet.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) runs DART, deep-ocean buoys that measure pressure changes, and the network supports tsunami detection.

DART data help modelers refine forecasts, but they cannot help communities that face a wave generated right at the shoreline.

Taken together, the TU Berlin catalog explains why fjords and reservoirs can make record heights, even when the triggering event is an earthquake.

Better seafloor maps, smarter local monitoring, and DART measurements can narrow uncertainty, but most communities still need fast self-evacuation plans.

The study is published in Natural Hazards.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–

Rate this article

Login to rate this article

Comments

Please login to comment

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!