Space & Astronomy

17 min read

Unraveling the Mysteries of Jupiter and Saturn's Strange Polar Storms

Earth.com

January 20, 2026•2 days ago

AI-Generated SummaryAuto-generated

A new study explains the differing polar storm patterns on Jupiter and Saturn. Researchers propose that the storms' origins lie deep within the planets' interiors. A softer vortex base, linked to lighter internal material, results in multiple smaller storms like Jupiter's. Conversely, a harder base, with denser material, leads to a single, massive storm, as seen on Saturn.

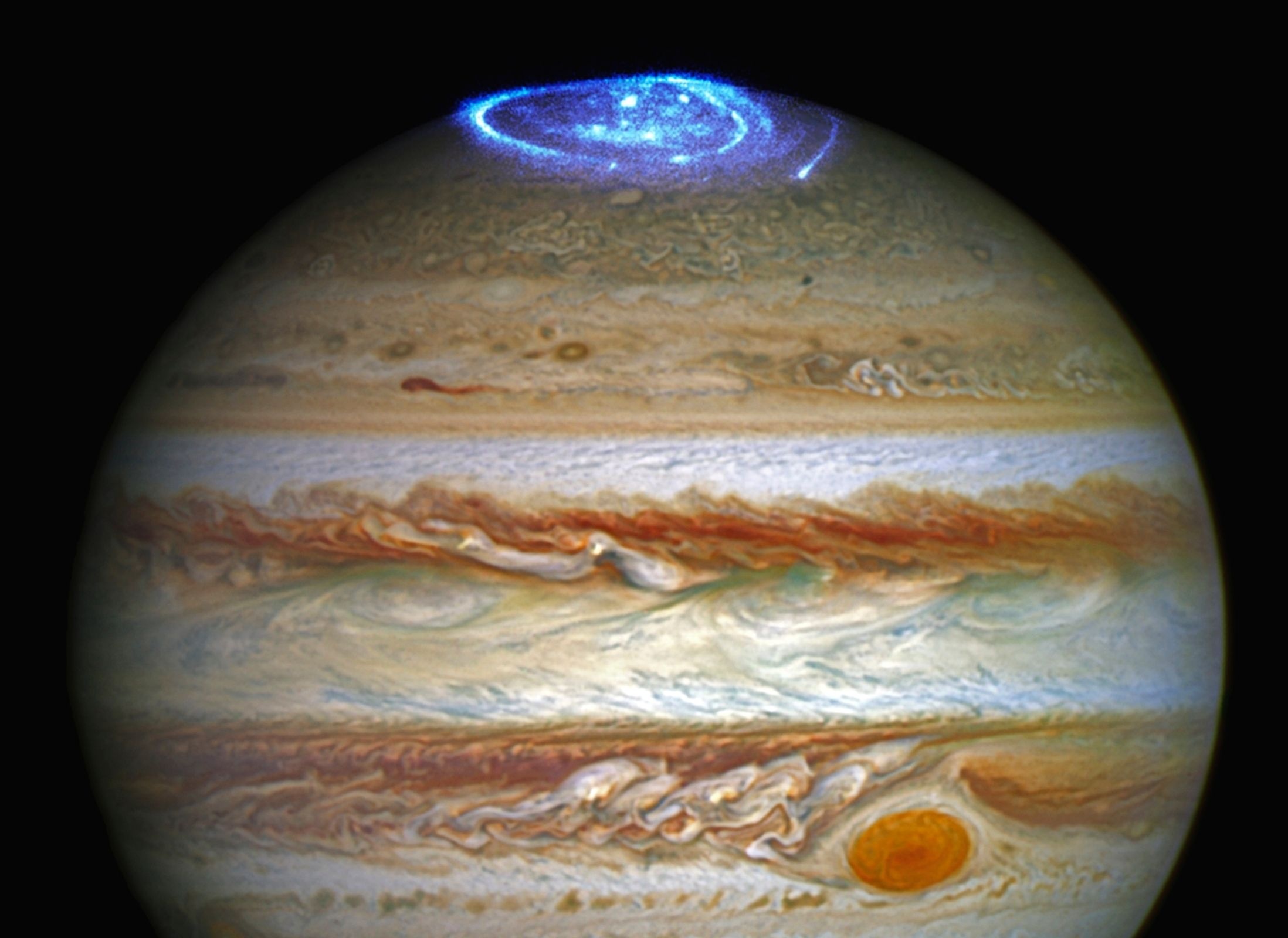

Strange storms swirl above the poles of Jupiter and Saturn. Spacecraft images show massive spinning weather systems that look nothing alike.

One planet hosts a single giant storm, while the other shows many smaller ones packed together.

For years, scientists wondered why two planets that look so similar behave so differently at their poles. A new study offers a clearer, simpler explanation.

Polar storms look different

Polar vortices are huge spinning storms that sit above a planet’s north or south pole. On Saturn, one enormous vortex covers the north pole and forms a neat six-sided shape.

On Jupiter, a large central vortex sits in the middle, surrounded by eight smaller swirling storms. Both planets share similar size and composition, which makes this contrast even more puzzling.

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) now suggest that the answer may lie deep beneath the clouds.

Looking beyond the clouds

Jupiter and Saturn both belong to a group called gas giants. These planets consist mostly of hydrogen and helium, instead of solid ground.

Space missions such as NASA’s Juno and Cassini have captured detailed images of the planets’ poles, revealing storm systems larger than Earth itself.

Jupiter’s polar vortices stretch about 3,000 (about 4,800 kilometers) miles across. Saturn’s single vortex is far larger, reaching nearly 18,000 miles (about 29,000 kilometers) wide.

Scientists have long tried to understand why one planet forms many storms while the other forms just one.

The research team explored how different vortex patterns can form from random motion in a gas giant’s atmosphere. Instead of focusing only on surface winds, the work links visible weather to the planet’s interior.

This connection helps explain not just how storms form, but what might exist deep inside these distant worlds.

Simulating giant polar storms

The research team used computer simulations to study how polar vortices grow. A simulation allows scientists to recreate complex systems using math and physics. In this case, the simulations modeled how gas flows over a rotating planet.

A polar vortex works like a spinning cylinder that stretches through many layers of atmosphere. The base of this spinning column reaches deep into the planet.

According to the study, the material at the bottom of the vortex plays a major role in shaping surface storms.

Wanying Kang is an assistant professor in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS).

“Our study shows that, depending on the interior properties and the softness of the bottom of the vortex, this will influence the kind of fluid pattern you observe at the surface,” said Professor Kang.

“I don’t think anyone’s made this connection between the surface fluid pattern and the interior properties of these planets. One possible scenario could be that Saturn has a harder bottom than Jupiter.”

Material controls polar storm size

In the simulations, the team tested many conditions. Some scenarios allowed only small vortices to form. Others led to one massive storm that absorbed all nearby motion. One key factor stood out in every case: the softness of the vortex base.

A soft base consists of lighter material. When gas at the bottom of a vortex stays light and flexible, the storm cannot grow too large. Several smaller vortices can exist side by side. This matches what scientists see on Jupiter.

A harder base contains denser material. In this case, a vortex can grow much larger and pull in surrounding storms. Over time, smaller vortices disappear, leaving behind a single giant system like Saturn’s polar storm.

This idea suggests that Saturn’s interior may contain heavier elements, while Jupiter’s interior may remain softer and lighter.

Why two dimensions work

A polar vortex exists in three dimensions, but the team simplified the problem using a two-dimensional model.

Fast rotation causes gas motion to line up along the rotation axis, which makes surface behavior easier to study in fewer dimensions.

“In a fast rotating system, fluid motion tends to be uniform along the rotating axis,” noted Professor Kang.

“So, we were motivated by this idea that we can reduce a 3D dynamical problem to a 2D problem because the fluid pattern does not change in 3D. This makes the problem hundreds of times faster and cheaper to simulate and study.”

What the surface can reveal

After running many simulations, one clear pattern emerged. The softness or hardness of material deep inside a planet shapes the storms visible at the surface.

“What we see from the surface, the fluid pattern on Jupiter and Saturn, may tell us something about the interior, like how soft the bottom is,” said Jiaru Shi, an MIT graduate student and the study’s first author.

“That is important because maybe beneath Saturn’s surface, the interior is more metal-enriched and has more condensable material which allows it to provide stronger stratification than Jupiter. This would add to our understanding of these gas giants.”

By linking surface storms to interior structure, this study opens a new way to study planets that humans may never visit.

The study is published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–

Rate this article

Login to rate this article

Comments

Please login to comment

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!