Health & Fitness

13 min read

Glutamate Levels Linked to Psychosis Onset in New Study

Managed Healthcare Executive

January 18, 2026•4 days ago

AI-Generated SummaryAuto-generated

A study on treatment-naive patients found elevated glutamate levels in the medial prefrontal cortex during first-episode psychosis, which normalized over time. This finding challenges existing views and suggests glutamate surges are disease-related, not drug-induced. The results may inform targeted therapies for early psychosis, potentially stratifying patients by glutamate levels for personalized treatment.

Recent research has provided new understanding into the progression of schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, offering prospects for more targeted treatment strategies. According to a study published in January in JAMA Psychiatry, scientists observed that glutamate concentrations in a critical brain region increase during the early stages of psychosis but return to normal levels over time, even in the absence of antipsychotic medication. These results challenge established perspectives on the course of these conditions and may impact novel therapeutic approaches.

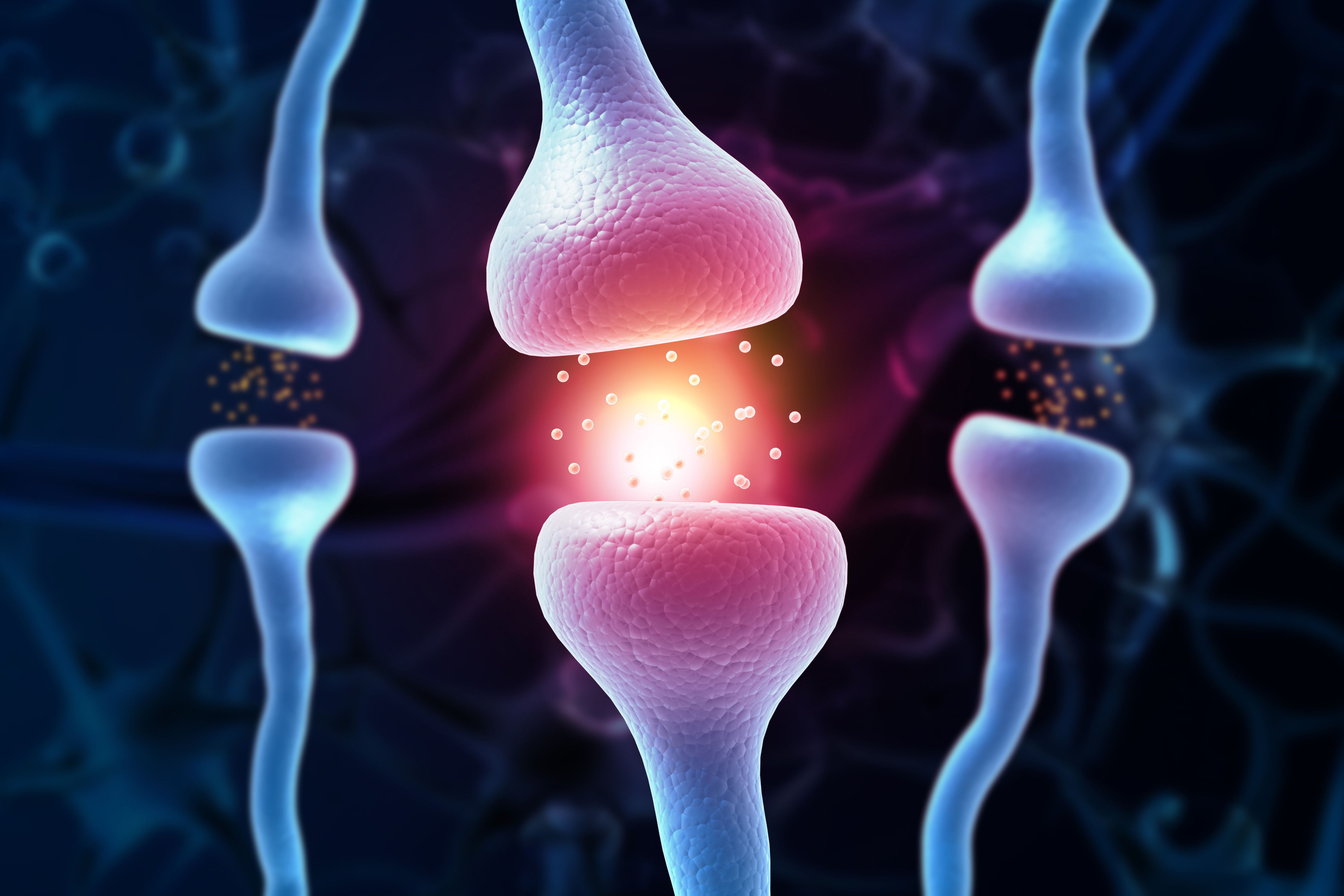

Glutamate is an excitatory neurotransmitter that interacts with several types of receptors found in the central nervous system.

The cross-sectional study, led by Luis Rivera-Chávez, M.D., at the Instituto Nacional de Neurología y Neurocirugía in Mexico City, Mexico, examined 181 participants: 65 with first-episode psychosis (FEP), 42 with chronic schizophrenia, and 74 healthy controls. All patients were treatment-naive, meaning they had never taken antipsychotics. Restricting the study to treatment-naive patients allowed researchers to isolate changes due to natural disease changes. Using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy, a noninvasive imaging technique, they measured glutamate in the medial prefrontal cortex, a brain area tied to cognition and emotion.

After excluding data from 38 participants due to movement or poor scan quality, the team analyzed results from 83 patients and 60 controls. Glutamate levels varied significantly among groups. Those with first-episode psychosis showed notably higher levels compared to both chronic schizophrenia patients and controls, with effect sizes indicating moderate to large differences. No significant gap existed between the chronic group and controls.

Higher glutamate in the first-episode psychosis group also correlated with poorer verbal and visual learning scores, though these associations were not present after adjusting for multiple tests.

Schizophrenia affects 1% of people worldwide and is a leading cause of disability, resulting in significant healthcare costs due to hospital stays, medication, and reduced productivity. Treatment usually relies on antipsychotic drugs that target dopamine D2 receptors. Those drugs are effective at reducing positive symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions. But approximately about 1 in 3 patients do not respond well to these medications, and they offer little improvement for negative symptoms like withdrawal or for cognitive impairments.

The glutamate hypothesis, proposed many years ago, suggests that problems with NMDA glutamate receptors may be responsible for all types of schizophrenia symptoms. This theory also explains why drugs — such as ketamine — that block NMDA receptors can produce effects like those seen in schizophrenia when taken by healthy individuals.

This context makes the new findings timely. Past research has linked elevated glutamate to early psychosis, but most studies involved medicated patients, obscuring whether changes stem from the disease or drugs. By focusing on never-treated individuals, the team provided clearer evidence that glutamate surges early on, independent of antipsychotics. This aligned with meta-analyses showing similar patterns in high-risk individuals and those with first-episode psychosis but not in established schizophrenia.

The study highlighted metabotropic glutamate receptor 2/3 (mGlu2/3) agonists, like the discontinued pomaglumetad, which failed in broad trials but showed promise in early-disease subgroups. Resuming trials with patient stratification, based on illness phase and glutamate scans, could yield a cost-effective choice, according to Rivera-Chávez and his colleagues.

The study had limitations. It could not differentiate glutamate from metabolic pools and only examined the prefrontal cortex. Further longitudinal research could help determine if these changes predict treatment response.

Rivera-Chávez’s team called for a renewed focus on glutamate-modulating drugs, tailored to disease stage. They note that not all first-episode patients had elevated levels, suggesting perhaps the need for personalized approaches.

Rate this article

Login to rate this article

Comments

Please login to comment

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!