Space & Astronomy

27 min read

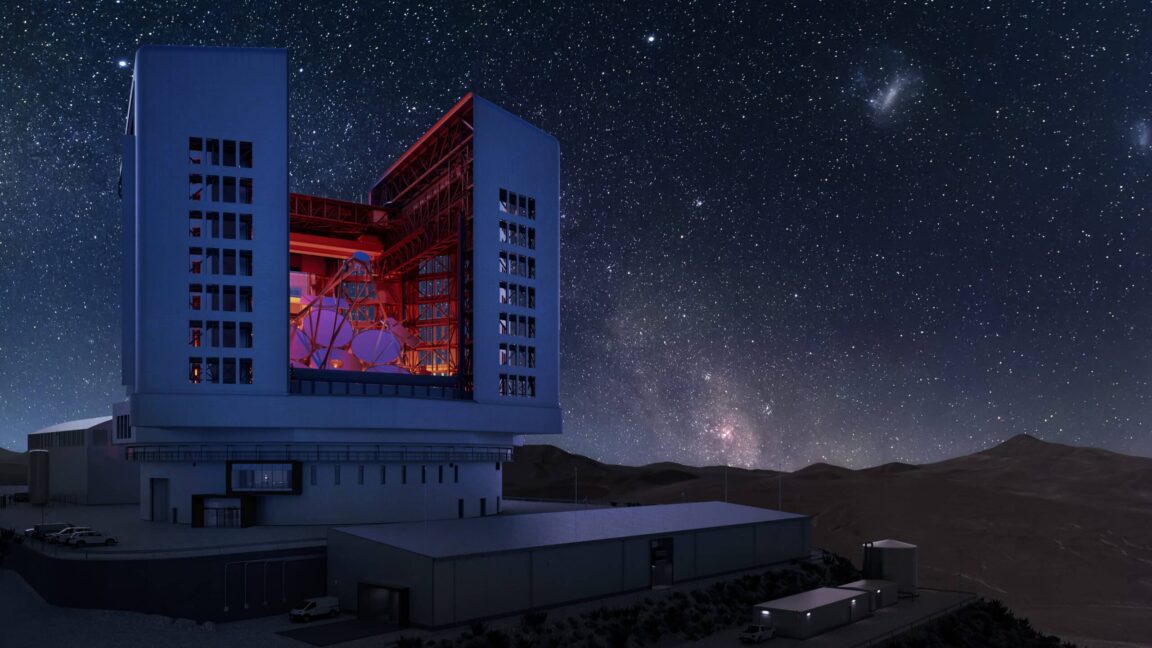

The Fierce Race for the Next Super-Large Ground Telescope

Ars Technica

January 19, 2026•3 days ago

AI-Generated SummaryAuto-generated

The Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT) is nearing completion, facing challenges but remaining a key competitor in building next-generation ground-based observatories. Despite delays and a significant cost, its advanced capabilities, particularly in spectroscopy, will allow detailed exoplanet atmosphere studies. The GMT aims to keep US astronomy competitive and drive technological innovation.

I have been writing about the Giant Magellan Telescope for a long time. Nearly two decades ago, for example, I wrote that time was “running out” in the race to build the next great optical telescope on the ground.

At the time the proposed telescope was one of three contenders to make a giant leap in mirror size from the roughly 10-meter diameter instruments that existed then, to approximately 30 meters. This represented a huge increase in light-gathering potential, allowing astronomers to see much further into the universe—and therefore back into time—with far greater clarity.

Since then the projects have advanced at various rates. An international consortium to build the Thirty Meter Telescope in Hawaii ran into local protests that have bogged down development. Its future came further into question when the US National Science Foundation dropped support for the project in favor of the Giant Magellan Telescope. Meanwhile the European Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) has advanced on a faster schedule, and this 39.5-meter telescope could observe its first light in 2029.

This leaves the Magellan telescope. Originally backers of the GMT intended it to be fully operational by now, but it has faced funding and technology challenges. It has a price tag of approximately $2 billion, and although it is smaller than the European project, the 25.4-meter telescope now represents the best avenue for US-based astronomy to remain competitive in the field.

Given all of this, I recently spoke with University of Texas at Austin astronomer Dan Jaffe, who is the new president of the telescope’s executive team, to get an update on things. Here is a lightly edited transcript of our conversation.

Ars Technica: What should we know about the Giant Magellan Telescope?

Dan Jaffe: This is going to be one of the premier next-generation optical infrared telescopes in the world. It will give the United States astronomical community access that helps us to be a leading nation in this field, inspire students to go into science and engineering, and really enrich the human experience through the new knowledge that we get about the nature of the universe. So I think it covers both this kind of aspiration that we have to enrich humanity in some way, to help foster the future economy by bringing more people into these technical fields, and also by driving technology in some areas. The kinds of work we’re doing on adaptive optics, for example, in building sensitive detector systems and spectrometers, drive the frontier of what you can do with these systems.

Ars: Why has this taken so long?

Jaffe: Well, it’s large, it’s complicated, and it’s unique. Those are the three things together that drive that. It involves a large amount of technology that’s needed to make something like this go in terms of size and precision and speed. And those things together make it take a long time, and also cost a fairly large amount of money. We’ve raised about half of the money. And many of the most difficult parts of the project are well underway in terms of construction or prototyping. All seven mirrors that are needed for the telescope are cast, and a number of them are already finished.

Ars: How is the telescope’s site in the Atacama Desert in Chile coming along?

Jaffe: We’ve broken ground on the site, and it’s been leveled in the foundation. Areas have been dug out, and the utilities have all been installed. It’s now kind of in a free state, waiting for some of the other parts of the project to catch up to it.

Ars: Since the European telescope is now likely to be completed first, does that mean GMT will miss out on a lot of science discoveries?

Jaffe: These telescopes are complementary in many ways. It depends not just on the glass itself, but on the instruments you put behind them, and what they’re capable of. And I expect that at this size scale there’ll be plenty of discoveries for all of us to make. And also with other things coming online, like the (Vera) Rubin telescope that will provide new types of phenomena to investigate, there won’t be a list of things we’ve got to do, and the first person to get to the finish line will do them. I think there’s going to be exciting science for all of us. Our community is growing right now. MIT and Northwestern have joined our consortium in the last year-and-a-half or two years, and I think we’re going to have plenty of very exciting science to do. As a public-private partnership for the whole US community, there’s a tremendous amount of brain power out there to be creative about new things and to be innovative, both in the kind of instrumentation we build and in the ways we use it.

Ars: How concerned are you about megaconstellations impacting observations by GMT?

Jaffe: Astronomers have always had to manage sources of noise including satellites, high-energy particles detected by instruments, and electronic noise. We address these with a variety of well-tested observing strategies and data-processing techniques that generally mitigate such issues very effectively. Satellites are most problematic for telescopes that are specifically designed to do surveys that cover wide areas of the sky and focus on imaging, not spectroscopy. The data and discoveries from these projects become the input and starting points for research on larger telescopes. The Giant Magellan Telescope will focus on spectroscopy of objects over small fields of view compared to a survey telescope—even when those targets are spread across wide areas of the sky. As a result, we are far less affected than large survey telescopes. We are, of course, always working to further improve our observing and data-processing strategies. At the same time, the astronomical community is working collaboratively with satellite operators to reduce their impact on science by altering satellite brightness and altitude and improving prediction and tracking. We’re confident that continued cooperation will allow ground-based astronomy to advance and coexist successfully with satellite technologies.

Ars: What are you most excited to observe with the telescope?

Jaffe: My own interest is in studying planetary systems, how they evolve, and how they form planets. And there I would say the giant telescopes, in particular the GMT because the implementation it has, will help to move us from a discovery phase to an investigation phase, where we try to learn about these planets around other stars. What are they made of? How hot are they? How are their atmospheres behaving? Things like that. So the capabilities of this telescope will put us into an era in the exoplanet world of really starting to learn about the nature of these exoplanets, not just finding more.

Ars: What kinds of things could we learn?

Jaffe: Well, in particular with my instrument, which breaks up the light into very fine intervals, you can study which molecules are present in exoplanet atmospheres much more precisely, and the ratio of the different isotopes, which tells you about where those molecules came from. You can measure temperatures. You can look at wind velocities. There are many, many things you can do that help you to study these planets in much more detail.

Ars: We’ve got this new generation of ground-based observatories coming online. What could we be doing with new space telescopes to complement this?

Jaffe: Generically, I would say there are two things you can do in space that are particularly helpful for ground-based astronomy. You can look at wavelengths that you can’t see from the ground. So ultraviolet and X-rays, in particular, are very important in that respect. The other thing is that you can look at things continuously, if you are in certain types of orbits. And so people are building a number of very small, specialized telescopes to just look at things for a long time. The Kepler observatory is a great example of this, for looking for those little dips as planets move in front of their host stars, something that people do from the ground, but it’s much, much harder. So depending upon the field, there are various complementary space projects of different scale that could be important. And you know, the GMT will follow-up on some of the discoveries with the James Webb Space Telescope. We have higher spatial resolution, so we’re able to look in more detail at some of the objects that were looked at there. We have different types of instrumentation that were not thought of when JWST was developed that can help with things. And I think the reverse will happen, as you were alluding to, that as we start to move into this era with the Giant Magellan Telescope, that this will engender certain types of space experiments that are that are targeted to the kinds of questions that we raise.

Rate this article

Login to rate this article

Comments

Please login to comment

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!