Space & Astronomy

19 min read

Cosmic Grapes: An Early Universe Galaxy Built in Pieces

Earth.com

January 20, 2026•2 days ago

AI-Generated SummaryAuto-generated

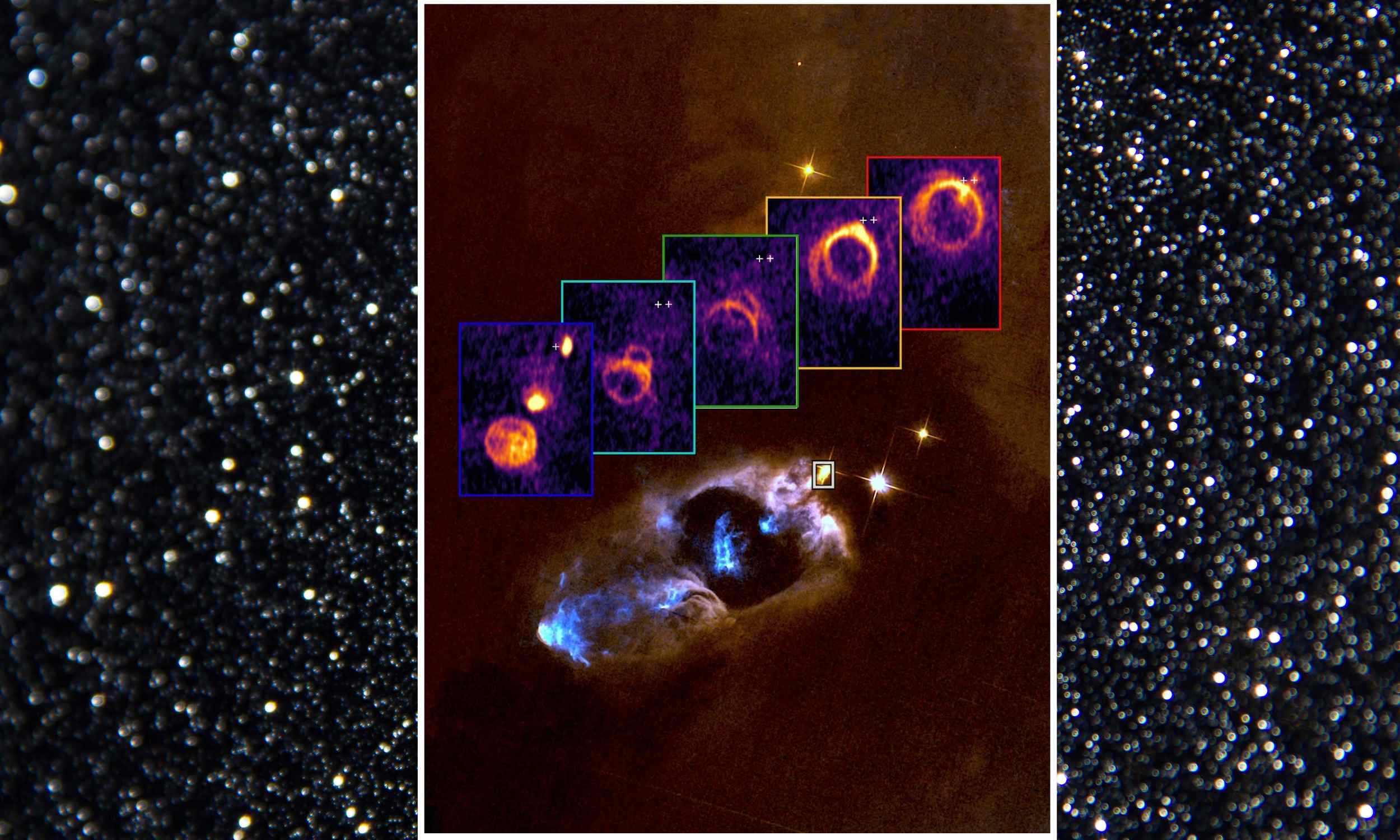

The "Cosmic Grapes" galaxy, observed 900 million years after the Big Bang, reveals a disk structure composed of multiple dense, star-forming clumps. This finding challenges existing theories on early galaxy formation and disk stability, suggesting that such galaxies may be more fragmented than previously understood. The discovery was made possible through gravitational lensing and combined telescope data.

A surprisingly orderly galaxy from the universe’s infancy, nicknamed “Cosmic Grapes,” shows signs of being built in pieces rather than as a smooth whole.

Its structure challenges long-standing ideas about how early galaxies grew and how stable their disks could be so soon after cosmic beginnings.

Studying the “Cosmic Grapes”

The Cosmic Grapes galaxy is a rotating system that formed about 900 million years after the Big Bang, with its disk split into multiple dense, star-forming clumps.

Earlier Hubble images showed a single, smooth disk, because limited resolution blurred small features into one patch of light.

Dr. Seiji Fujimoto at the University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin) led an analysis that combined gravitational lensing with telescope data.

His team studies how early galaxies build disks, and the Cosmic Grapes galaxy suggests even normal disks can hide many clumps.

A foreground galaxy cluster used gravitational lensing, which is when gravity bends and brightens distant light, to make the Cosmic Grapes galaxy appear larger.

Earlier lens models in a detailed preprint estimated magnification high enough to map the galaxy’s interior.

“This object is known as one of the most strongly gravitationally lensed distant galaxies ever discovered,” said Dr. Fujimoto.

ALMA and Web join forces

Long-wavelength light carries clues about the material that forms stars, especially cold gas and dust.

The Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) is an interferometer, dishes working together as one telescope, to sharpen detail at long wavelengths.

ALMA maps where that cold material sits, and those maps help explain why some clumps form stars so quickly.

Dust blocks visible starlight, yet longer wavelengths can escape and reveal young stars forming deep inside galaxies.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) uses infrared, light longer than visible wavelengths, gathered by a 21.3-foot mirror (6.5 meters).

In the Cosmic Grapes galaxy, JWST separated bright clumps from older surrounding stars, tightening estimates of age and mass.

Rotation forms clumps

Gas motion across a galaxy shows whether its parts share a common orbit or belong to a chaotic merger.

More than 100 hours of observing time let researchers track kinematics, motion measured from line-of-sight speeds, across the rotating disk.

That rotation ties each clump to the same system, so the structure reflects how disks grew early on.

Inside the rotating disk, at least 15 star-forming clumps crowd together, far more than computer simulations that model evolving galaxies allow.

Each clump holds dense gas, and that density helps gravity win over pressure, letting clouds collapse into new stars.

Because the galaxy looks otherwise ordinary, the clumps may be common, yet many remain hidden without lensing.

Why the clumps form

Sharper detail matters because early galaxies pack many events into small spaces, and blended light can hide separate structures.

Using lensing support, the team reached spatial resolution, the smallest detail a telescope can separate, of about 30 light-years (176 trillion miles).

At that scale, researchers could count individual clumps and compare their sizes directly with star-forming regions nearby today.

Gas-rich disks can break into pieces when internal support cannot counter the pull of the disk’s own gravity.

Astronomers call this gravitational instability, when gravity overwhelms pressure and rotation, and it naturally produces compact clumps.

Models that limit such fragmentation may be missing key physics, especially in galaxies that have not yet settled down.

Main sequence, not odd

Most star-forming galaxies follow a steady pattern between how much mass they hold and how quickly they make stars.

Astronomers call that pattern the star-forming main sequence, a typical link between mass and star-formation rate, and the galaxy sits on it.

That normal status means theorists must explain clumps without blaming unusual conditions, like rare bursts or violent mergers.

Where simulations fall short

Computers build virtual galaxies by turning equations into code, then stepping them forward in time under gravity and gas physics.

Many models smooth the gas too much or inject strong heating, and either choice can erase small clumps early.

The Cosmic Grapes galaxy suggests those settings may need adjustment, but changes must still match other galaxy statistics.

Feedback under pressure

Young stars do not just shine, because they also push and heat surrounding gas through radiation and exploding supernovas.

Astronomers group those effects as stellar feedback, energy and momentum from stars, and it can break up dense clouds.

If feedback is weaker in some early disks, long-lived clumps could grow, but that idea needs more tests.

What better resolution means

Turning stretched images into real shapes requires careful math, because lensing distorts positions as well as brightness.

A lensing model, a map of how magnification changes, let the team reconstruct the galaxy’s disk in its own frame.

That reconstruction reduces confusion between true clumps and lens artifacts, setting a higher bar for future surveys.

Lessons from the Cosmic Grapes

More strongly lensed galaxies will let astronomers repeat the test, looking for disks that break into many compact clumps.

Future work from UT Austin and partner teams can compare clumps across ages, using ALMA and JWST to keep measurements consistent.

If the pattern holds, theorists will need new recipes for early disks, and observers will know where to look.

Taken together, the lensing, multiwavelength data, and rotation maps show early disks could be structured without being rare.

Better simulations and more lensed targets should pin down which physics makes clumps survive, and which quickly dissolve.

The study is published in Nature Astronomy.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–

Rate this article

Login to rate this article

Comments

Please login to comment

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!