Health & Fitness

19 min read

Beige Fat: The Surprising Guard Against High Blood Pressure

Earth.com

January 18, 2026•4 days ago

AI-Generated SummaryAuto-generated

New research reveals beige fat plays a crucial role in regulating blood pressure. Studies in mice show that when beige fat loses its thermogenic identity, an enzyme called QSOX1 is overproduced. This leads to vascular stiffening and elevated blood pressure, independent of obesity. The findings suggest therapies targeting this fat-vessel communication could help manage hypertension.

Obesity and high blood pressure often show up together. Then heart trouble follows. It’s a grim chain, and it matters because cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death worldwide.

For a long time, the big question was simple: why? People knew extra body fat was linked to hypertension, but the biological “how” stayed fuzzy.

Fat seemed like passive storage, just sitting there. A new study says it’s anything but passive, and that one specific kind of fat can push blood pressure up or help keep it in check.

Not all fat plays the same role

The work centers on thermogenic beige fat. This is a type of adipose tissue that helps the body burn energy. It’s different from white fat, which mainly stores calories.

Beige fat acts more like brown fat, the heat-making fat found in newborns and many animals, and also found in some adults, often around the neck and shoulders.

This matters because earlier clinical evidence showed that people with brown fat have lower odds of hypertension. This evidence could only show a relationship, not proof that brown or beige fat was actually driving the difference.

To get that proof, the researchers needed a setup where everything stayed the same except the type of fat.

A mouse model with one focus

Paul Cohen heads the Weslie R. and William H. Janeway Laboratory of Molecular Metabolism and treats patients at Memorial Sloan Kettering.

Cohen’s team built mouse models that could not form beige fat, which in mice is the thermogenic fat depot that most closely resembles adult human brown fat.

“We’ve known for a really long time that obesity raises the risk of hypertension and cardiovascular disease, but the underlying biology has never been fully understood,” said Cohen.

“We now know that it’s not just fat, per se, but the type of fat – in this case, beige fat – that influences how the vasculature functions and regulates the whole body’s blood pressure.”

The team focused on beige fat identity. They deleted a gene called Prdm16 only in fat cells. The mice stayed healthy in every way except for one key trait: their fat cells couldn’t keep a beige identity.

“We knew there was a link between thermogenic adipose tissue – brown fat – and hypertension, but we had no mechanistic understanding of why,” said Mascha Koenen, a postdoctoral fellow in the Cohen lab.

When beige fat disappears

The results didn’t look subtle. Fat around the blood vessels in these engineered mice started acting more like white fat.

That shift came with markers of white fat, including angiotensinogen, a precursor to a major hormone that increases blood pressure.

The mice showed elevated blood pressure and mean arterial pressure. Their blood vessels also changed physically. Tissue analysis showed stiff, fibrous material building up around vessels.

When the researchers tested arteries from these animals, the vessels reacted with unusual force to angiotensin II, one of the body’s strongest blood pressure signals.

In other words, the system that tightens blood vessels had become touchy and overreactive.

“We didn’t want the model to be analogous to an obese versus lean individual,” explained Koenen. “We wanted the only difference to be whether the fat cells in the mouse were white or beige. In that way, the engineered mice represent a healthy individual who just happens to not have brown fat.”

That clean design made the message hard to ignore: losing beige fat identity alone can tip blood pressure upward, even without obesity or inflammation muddying the waters.

A hidden enzyme flips the switch

So what, exactly, carried the message from altered fat to altered blood vessels?

The team used single-nucleus RNA sequencing and saw that, without beige fat, vascular cells turned on a gene program tied to stiff, fibrous tissue.

That kind of stiffening makes vessels less flexible, forces the heart to pump harder, and raises blood pressure.

The researchers narrowed in on a signal coming from the fat cells themselves. They tested secreted mediators released by fat cells that lacked beige identity.

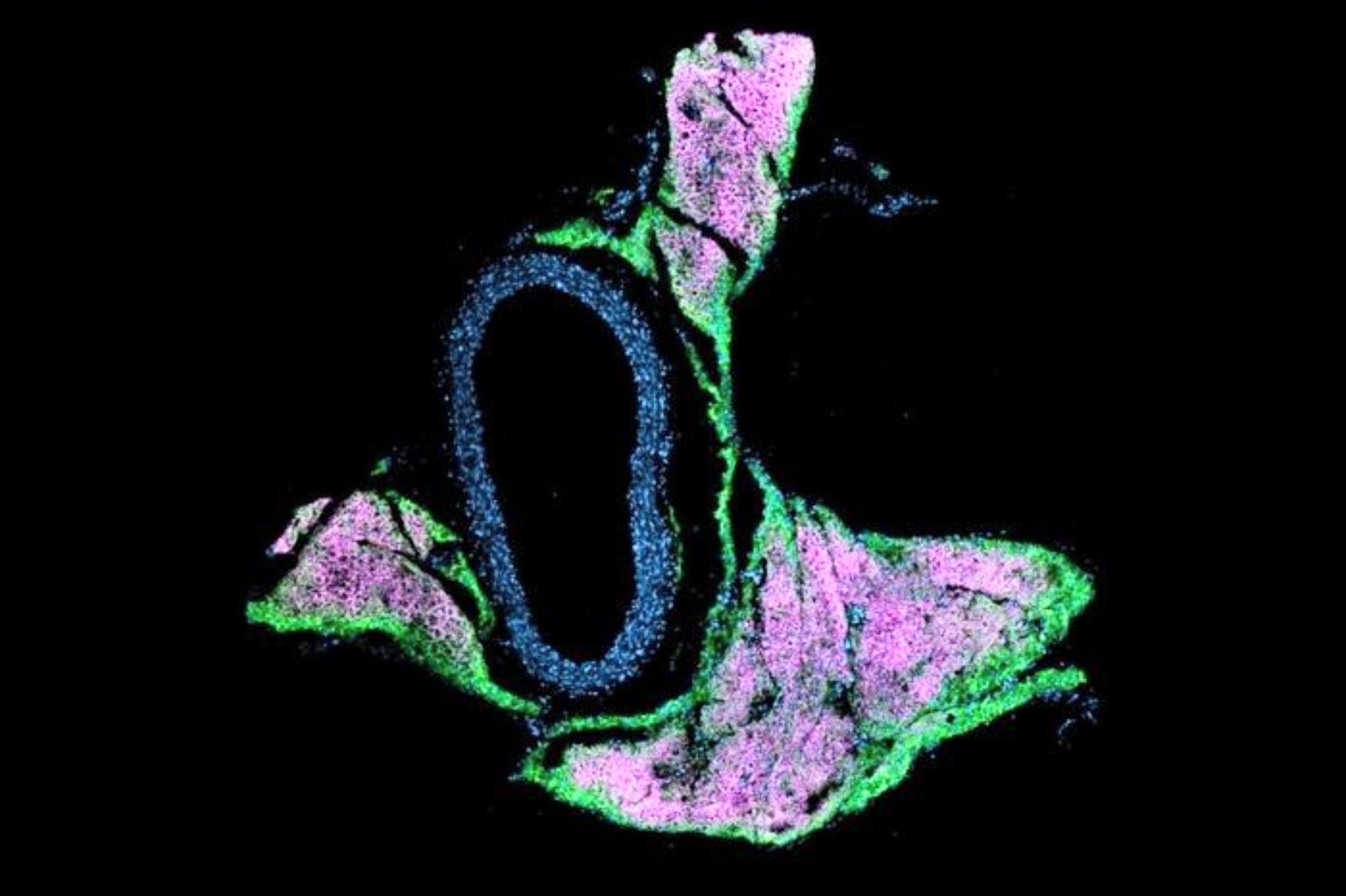

When beige fat loses its identity

The results showed that transferring this fluid onto vascular cells could activate the fibrous-tissue gene program on its own. That pointed to something in the “soup” that fat cells release.

Using large gene and protein expression datasets, the researchers identified one enzyme: QSOX1. It has been tied to tissue remodeling in cancer.

The key twist is that beige fat normally keeps QSOX1 turned off. When beige identity is lost, QSOX1 gets overproduced, and a cascade begins that ends in hypertension.

To check that QSOX1 wasn’t just along for the ride, the team engineered mice missing both Prdm16 and Qsox1.

Those mice, as expected, had no beige fat, but they also did not develop vascular dysfunction. That result put QSOX1 in the driver’s seat.

The study doesn’t stop at mice. In large clinical cohorts, people carrying mutations in PRDM16 showed higher blood pressure.

That lines up with the mouse results, where loss of Prdm16 switched on QSOX1 and pushed the system toward hypertension.

The researchers describe this approach as reverse translation: a physician-scientist sees a pattern in patients, then uses lab models to figure out the mechanism, then brings that understanding back to human disease.

Here, the method uncovered a direct line of communication between fat and blood vessels that does not depend on obesity itself.

The practical promise is more specific treatment ideas. High blood pressure already has many effective drugs, including ones that target angiotensin signaling.

This work suggests another angle: therapies that target the molecular conversation between thermogenic fat and the vessel wall, possibly including QSOX1.

“The more we know about these molecular links, the more we can move towards conceiving of a world where we can recommend targeted therapies based on an individual’s medical and molecular characteristics,” said Cohen.

The full study was published in the journal Science.

Image Credit: Weslie R. and William H. Janeway Laboratory of Molecular Metabolism at The Rockefeller University

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–

Rate this article

Login to rate this article

Comments

Please login to comment

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!